L17-01

The Gleki's

|

||

Crash-course in Lojban

|

This tutorial gives a gentle introduction to Lojban, a logical language. 17 lessons of this course will allow you to understand most of the Lojban you are likely to see in the online Lojban discussion groups or publications.

Lojban is a constructed language based on so called predicate logic which makes it kind of a bridge between different languages and cultures.

Whereas natural grown languages have complications in grammar rules, biases and restrictions Lojban is designed to free us from them thus encouraging other ways of thinking otherwise unreachable.

Therefore, it allows us to see the world brighter.

- Lojban is clean, simple, and at the same time powerful language. Why not start speaking it?

- Lojban speech allows you to say things shorter without unnecessary distracting details. For example, you don't have to always think of what tense (past, present or future) to use in a verb when it's already clear from context. When you need details you add them. But unlike other languages Lojban doesn't force you to do so.

- Lojban is for artists because Lojban has unprecedented tools for expressing tiny details of human emotions

- Lojban is for lovers of wisdom (philosophers, in the original sense)

- Lojban is for scientists that like all concepts to be put in a concise system.

- Lojban is the best tool for implementing machine automatic translation. Still it's a speakable language.

- Lastly, Lojban is also fun !

Lojban is going to change the way you look at verbal communication. Learning Lojban is much more than just learning it's words and grammar. Learning Lojban is more about understanding it. You will need to understand many things about the way languages work. If you are not a linguist, it will be new to you. If you are a linguist it'll strike you how different ideas and philosophies you familiar with can be directly uttered in the flow of normal speech.

Lojban will make you think about the ways you express ideas in words. Something that you learned and used every day but never tried to understand how it works.

If you are deciding which language to learn or whether to learn any at all, you need to define your goals. Being able to understand what is spoken or speak so that other speakers understand is a good reason to learn most other languages. Learning new ways of thinking and expression of thoughts is a good reason to learn Lojban.

Lojban is likely to be very different to the kinds of languages you are familiar with — which certainly include English. Learning Lojban may be easy or hard, depending on how well you understand the ideas behind it. There are not many words and rules that you need to learn to get into a basic level. You will get there rather quickly if you put a systemic effort. On the other hand, if you fail to understand some basic point, memorizing things will not help you much. In such cases don't hesitate to move on, and come back to it later. Likewise, some of the exercises are trickier than others (particularly the translation exercises at the end of each lesson). If you can't work out the answer to a particular question, feel free to skip it — but do look at the answer to the question, as there are often useful hints on Lojban usage in there. The answers to the exercises are at the end of each lesson.

Lojbanic text is always in bold.

Translations of Lojbanic sentences are in italic.

Explanations of the structure of text in Lojban is in such "square" letters.

Brackets are used to clarify the grammatical structure of Lojban in examples. [These brackets are not part of official Lojban orthography, and are included only for academic purposes].

- Examples are indented. This is an example of case study sentence.

For more information on Lojban, please contact the Logical Language Group:

- e-mail: thelogicallanguagegroup@gmail.com

- online IRC chat: Web chat

- web-site: mw.lojban.org

This course is created by the author Gleki with the help of the Lojban community throughout year 2015. It is loosely based on the book Complete Lojban Grammar, tutorials Wave Lessons and Lojban For Beginners. Important note: this textbook teaches simplified and optimized dialect of Lojban called La Bangu.

Lesson 1. Language at a glance

Alphabet

The basic thing you need to know about Lojban is obviously the alphabet.

Lojban uses the Latin alphabet (vowels are colored).

- a b c d e f g i j k l m n o p r s t u v x y z ' .

Most letters are pronounced like in English or Latin, but there are a few differences.

There are six vowels in Lojban.

| a | as in father (not as in hat) |

| e | as in get |

| i | as in machine or (Italian) vino (not as in hit) |

| o | as in bold or more — not as in so (this should be a ‘pure' sound). |

| u | as in cool (not as in but) |

These are pretty much the same as vowels in Italian or Spanish.

The sixth vowel, y sounds like both a in the word America. So it's kind of er or, in American English, uh. y is the sound that comes out when the mouth is completely relaxed (this sound is also called schwa in the language trade).

As for consonants

| c | is pronounced as sh (like in shop). |

| g | always g as in gum, never g as in gem |

| j | like j in French bonjour or like s in pleasure or treasure. |

| x | like ch in Scottish loch or as in German Bach, Spanish Jose or Arabic Khaled. Try pronouncing ksss while keeping your tongue down and you get this sound. |

| ' | like English h. So the apostrophe is regarded as a proper letter of Lojban and pronounced like an h. It can be found only between vowels. For example, u'i is pronounced as oohee (whereas ui is pronounced as ooh-eeh). |

| . | a full stop (period) is also regarded as a letter in Lojban. It's a short pause in speech to stop words running into each other. Actually any word starting with a vowel has a full stop placed in front of it. This helps prevent undesirable merging of two sequential words into one. |

Stress is always put on the last but one vowel or shown explicitly using symbol ` in order to break this rule. If a word has only one vowel you just don't stress it.

You don't have to be very precise about Lojban pronunciation, because the sounds are distributed so that it is hard to mistake one sound for another. This means that rather than one ‘correct' pronunciation, there is a range of acceptable pronunciation — the general principle is that anything is OK so long as it doesn't sound too much like something else. For example, Lojban r can be pronounced like the r in English, Scottish or French.

Two things to be careful of, though, are pronouncing Lojban i and u like Standard British English hit and but (Northern English but is fine!). This is because non-Lojban vowels, particularly these two, are used to separate consonants by people who find them hard to say. For example, if you have problems spitting out the ml in mlatu (which means cat), you can say mɪlatu — where the ɪ is very short, but the final i has to be long.

The simplest sentences

Now let's turn to constructing our first sentences in Lojban.

Of course one of your first thoughts might be "Where are nouns and verbs in Lojban?"

The word

- mlatu

is roughly translated as cat but it's more correctly to say that it means

- to be a cat

It's a verb. Two more verbs are

- pinxe

- to drink

and

- ladru

which is roughly translated as milk. But it's rather

- to be a quantity of milk

It might sound strange how cat and milk can be verbs but in fact this makes Lojban very simple.

Let's imagine we want to say A cat drinks milk.

To turn a verb into a noun we put a short word lo in front of it. And to show a verb we put the word cu in front of the verb.

- lo mlatu cu pinxe lo ladru

- A cat drinks milk.

Remember that c is pronounced as sh.

So we turned mlatu and ladru into nouns. We can also say that lo creates a noun from a verb with roughly the meaning of one who does (the action of that verb).

And by using cu we show that the next word, i.e. pinxe is still a verb.

Any verb can be turned into a noun. For example, lo pinxe will mean a drinker. Template:TalkquoteGreen Now let's talk about pronouns like I and you.

- mi = I

- do = you

- ra = he, she or they

- mi'ai = we

- ti = this one, this object near me.

- ta = this one, this object near you.

- tu = that one, that object over there.

Like their English name hints, pronouns work like nouns by default. And they don't require lo in front of them.

- mi pinxe

- I drink.

- do pinxe

- You drink.

- ti ladru

- This is milk.

- tu mlatu

- That is a cat.

As you can see we can even omit cu after pronouns as we can clearly see the pronoun and the verb being separated.

As nouns and pronouns work exactly the same we'll always call them nouns later for brevity.

Unlike English we don't have to add the verb "is/are" to the sentence. Everything is already there: mlatu means to be a cat.

Compound verbs

Now let's talk about compound verbs.

tanru or compound verbs are a powerful tool that can give us richer verbs. You just string two verbs together. And the left part of such compound verb adds a flavor to the right one.

For example,

- sutra

- to be fast

- sutra pinxe

- to quickly drink, to drink fast.

Here the verb sutra adds an additional meaning as it is to the left of another verb. As you can see seltau are translated using adverbs.

We can put lo to the left of such compound verb getting a compound noun. Seltau in noun form are translated using adjectives or participles:

- lo sutra pinxe

- a quick drinker.

Now you know why there was cu after nouns in our example

- lo mlatu cu pinxe lo ladru

- A cat drinks milk.

Without cu it'd turn into lo mlatu pinxe … with the meaning a cat-like drinker whatever that could mean.

Compound verbs can contain more than two verbs. In this case the first verb modifies the second one, the second one modifies the third and so on:

- lo sutra bajra mlatu

- A quickly running cat

where as

- lo sutra mlatu means

- A quick cat

and

- lo bajra mlatu means

- A running cat

Numbers

Now let's talk about numbers.

Amazing but we haven't said yet how many of our cats are actually drinking milk. The sentence

- lo mlatu cu pinxe lo ladru

- A cat drinks milk.

is vague in this regard. It can be one cat or even 25 cats drinking milk. Any of such interpretations are possible.

lo simply turned a verb into a noun but now we might want to specify the number.

Let's add a number in front of lo.

- pa means 1

- re - 2

- ci - 3

- vo - 4

- mu - 5

- xa - 6

- ze - 7

- bi - 8

- so - 9

- no - 0 (zero).

- ro - each, every.

- za'u - more than one, plural number

So

- pa lo mlatu cu pinxe lo ladru

- A cat/one cat drinks milk.

For numbers consisting of several digits we just string those digits together.

- re mu lo mlatu cu pinxe lo ladru

- 25 cats drink milk.

ro is also used to express the meaning of all.

- ro lo mlatu cu pinxe lo ladru

- Every cat drinks milk.

- All cats drink milk.

Yes, it's that simple.

Besides, we can say:

- ci lo re mu mlatu cu pinxe lo ladru

- Three out of 25 cats are drinking milk.

or

- ro lo re mlatu cu pinxe

All of two cats are drinking(literally)- Both cats are drinking.

So we use lo as a separator in phrases with out of or similar.

To say just cats as opposed to a cat (one cat) we use the number za'u.

- za'u lo mlatu cu pinxe

- Cats are drinking.

whereas

- pa lo mlatu cu pinxe is

- A cat is drinking.

Events

Now let's talk about events and how we express them. The word nu transforms a verb into an event or a process.

- pinxe

- to drink

- lo nu pinxe

- drinking

- dansu

- to dance

- lo nu dansu

- dancing

- jorne

- to connect

- lo nu jorne

- connection

- jimpe

- to understand, to comprehend

- lo nu jimpe

- understanding, comprehension

So lo nu corresponds to English -ing, -tion or -sion.

As usual we can add to the verb normal words like nouns, pronouns. In fact nu allows us to create a full phrase after itself.

- klama

- to come

- lo nu klama

- coming

- lo nu do klama

- coming of you

Some verbs require using events instead of ordinary nouns. For example

- gleki

- to be happy (because of some event).

- lo gleki

- a happy one, a happy person

- mi gleki lo nu do klama

- I'm happy because you are coming.

Some words are events by themselves.

- nicte

- (some event) is a nighttime.

- lo nicte

- night, nighttime

This is where we can see bare nu (without lo).

- lo nicte cu nu mi viska lo lunra

- The night is when I see the Moon.

- (The night is the event when I see the Moon).

where

- viska

- to see

- lo lunra

- the Moon

We can combine such words with events together so no lo nu will be used.

- lo cabna

- present time, (an event) is at present.

- lo cabna cu nicte

- Now it's night. At present it's night.

Prepositions and tenses

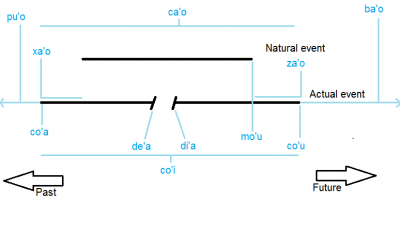

Now let's talk about prepositions related to tense.

- pu denotes past tense or before some event

- ca denotes present tense or at the same time as some event

- ba denotes future tense or after some event

And now examples:

- mi pinxe ca lo nu do klama

- I drink while you are coming.

Yes, we need lo nu to insert a whole sentence after ca.

- mi citka ba lo nu mi dansu

- I eat after I dance.

Now let's talk about tenses.

English forces us to use certain tenses. You have to choose between

- A cat drinks milk.

- A cat has been drinking milk.

- A cat drank milk.

- A cat will have drunk milk.

and other similar choices.

However, in Lojban you can be as vague or as precise as you want.

Our sentence

- lo mlatu cu pinxe lo ladru

- A cat drinks milk.

in reality says nothing about when this event happens. Context is clear enough in most cases and can help us. But if we need more precision we just add more words.

It may be a surprise to you but those prepositions can be used as tenses as well!

The only difference is that we should just drop the noun after pu, ca, ba and they turn into tenses.

So

- lo mlatu cu pinxe lo ladru ca

- The cat drinks milk (at present).

- lo mlatu cu pinxe lo ladru pu

- The cat drank milk.

- lo mlatu cu pinxe ba

- The cat will drink milk.

We can also put them before the the main verb.

So we can get

- lo mlatu ca pinxe lo ladru

- A cat (at present) drinks milk.

As you can see we replaced cu with ca as ca also clearly separates the previous noun from the verb.

However, we shouldn't say pu lo mlatu as with a noun after it this pu will turn into a preposition. And it would mean before the cat (in time). So here we should use the word nu.

- ba nu lo mlatu cu pinxe

- The cat will drink.

So we can put the word nu when we want to indicate tense in the beginning of a sentence thus separating it from the noun coming next.

Here are three more prepositions (we'll use them only as tenses for now for simplicity).

- ca'o — continuous tense

- ba'o — perfect tense

- ta'e — habitually

Now we can say even more precisely

- lo mlatu ca ca'o pinxe lo ladru

- A cat (at present) is drinking milk.

Here we get a very precise translation of an English sentence that has what is called Present Continuous tense in English.

There is also Present Simple tense that describes events that happen sometimes.

- lo mlatu ca ta'e pinxe lo ladru

- A cat (habitually, sometimes) drinks milk.

For Perfect we use ba'o.

- lo mlatu ca ba'o pinxe lo ladru

- A cat has drunk milk.

Of course we could omit ca in this sentence (I'm sure that the context would be clear enough in most such cases).

We can use the same rules for describing the past using pu instead of ca or the future using ba.

We can combine tenses with and without phrases after them.

- mi pu citka ba lo nu mi dansu

- I ate after I danced.

Note, that pu (past tense) is put only in the main phrase (mi pu citka).

We shouldn't put it with dansu (unlike English) as mi dansu is viewed relative to mi pu citka so we already know that everything was in past.

Let's take one more useful preposition.

- ze'a

- some (medium length of time), during, through some time.

- sipna

- to sleep

- lo nicte

- a nighttime

- mi pu sipna ze'a lo nicte

- I slept all night. I slept through the night.

Let's compare it with ca.

- mi pu sipna ca lo nicte

- I slept at night.

When using ze'a we are talking about the whole interval of what we describe. Don't forget that nicte is an event so we don't need nu here.

Other prepositions

Other prepositions work the same way.

- fa'a

- towards …, in the direction of ...

- to'o

- from …, from the direction of ...

- bu'u

- at ...(some place)

- se ja'e

- because ... (of something)

- mi klama fa'a do to'o lo mlatu

- I go to you from a cat.

The interesting thing about those directional prepositions is that you can freely move fa'a and to'o with nouns after them around the sentence as you like without changing the meaning.

- fa'a do mi ca klama to'o lo mlatu

- Towards you I go from a cat.

- to'o lo mlatu mi fa'a do ca klama

- From a cat I (towards you) go.

As you can see Lojban is very flexible.

One thing is important.

When using nu you create a separate phrase inside the big sentence. Be sure not to mix nouns and prepositions from different phrases and the big one. Here is an example:

- plipe

- to jump

- lo mlatu cu plipe fa'a mi ca lo nu do klama

- A cat jumps towards me when you come.

is the same as

- lo mlatu cu plipe ca lo nu do klama vau fa'a mi

- A cat jumps (when you come) towards me.

We use vau after each phrase when we want to show it's border.

However,

- lo mlatu cu plipe ca lo nu do klama fa'a mi

- A cat jumps (when you come towards me).

As you can see do klama fa'a mi is a phrase inside the big one. So fa'a mi is now inside it.

Now you, not the cat come towards me.

At the end of the sentence vau is never needed as it's already the right border.

Place structure

Lojban dictionaries present all verbs with x1, x2 etc. symbols as e.g.

- prami

- x1 loves x2

There is nothing strange in these x1, x2. They are called places and simply represent the order in which you have to add nouns. E.g.

- mi prami do

- I love you.

This also means that

x1 means to love and

x2 means to be a loved one.

The advantage of such style of definitions is that compared to English there is no need in many additional words as all participants of this love are in one definition.

We can also omit nouns making the sentence more vague:

- prami do (literally loves you) means Someone loves you.

Alternatively you can replace unnecessary places with the word zo'e = something/someone.

- zo'e prami do

- Someone loves you.

which will mean the same as prami do.

The place structure of compound verbs is the same as the of the last verb word in it:

- tu sutra bajra bruna mi

That is a quickly running brother of me- That is my quickly running brother.

So the place structure is the same as of bruna alone.

More than two places

There might be more than two places. E.g.

- pinxe

- x1 drinks x2 from x3

- mi pinxe lo ladru lo kabri

- I drink milk from a cup.

- lo kabri

- a cup

In this case there are three places and if you want to exclude the second place in the middle you have to use zo'e:

- mi pinxe zo'e lo kabri

- I drink [something] from a cup.

If we omitted zo'e we'd get

- mi pinxe lo kabri

- I drink a cup.

which would make no sense.

Relative clauses

Now about relative clauses. Let's look at these two sentences.

- The cat that is white is drinking milk.

- The cat, which is white, is drinking milk.

In the first sentence the word "that" is essential to identifying the cat in question. Out of probably many cats we look only at those who are white. May be there is only one cat around that is white.

As for "which is white" from the second sentence it just provides additional information about the cat. It doesn't help us to identify cats. For example, this might happen when all the cats are white.

In Lojban we use poi for the first sentence and noi for the second sentence.

(The word blabi means to be white).

- lo mlatu poi blabi cu pinxe lo ladru

- The cat that is white is drinking milk.

- lo mlatu noi blabi cu pinxe lo ladru

- The cat, which is white, is drinking milk.

This poi blabi is a relative clause, a mini-sentence attached to the noun lo mlatu. It ends just before the next word cu.

So we actually additionally state in the sentence that lo mlatu cu blabi - the cat is white.

Let's have a more interesting example.

lo tricu = a tree

barda = to be big/large

klama = to go to something

lo tricu noi mi klama ke'a cu barda

A tree, to which I go, is big.

Note that word ke'a. It refers to the noun to which our relative clause is attached.

So literally our Lojbanic sentence sounds like

"A tree, such that I go to which, is big".

Note that we can always extract this relative clause and make it an independent sentence by replacing ke'a with the noun to which this relative clause was attached.

So this big sentence also mention in passing that mi klama lo tricu = I go to a tree.

Terminology

Let's quickly mention the correct terms describing Lojban grammar and how Lojban sentences are constructed.

Nouns, pronouns and personal names act exactly the same way in Lojban. So we will call both of them nouns for simplicity. In Lojban they are called sumti (easy to remember, as it sounds a bit like someone saying 'something' and chewing off the end of the word).

The simplest phrase would be

- prami

- [Someone] loves.

Such short phrase can be useful sometimes. For example when you see a car coming you would simply say

- karce

- Car!

because the context will be clear enough that there is a car somewhere around and probably it's dangerous.

Or you can say

- vanci

in the sense

- It's getting dark.

although vanci just means evening.

All omitted places just mean zo'e = something/someone/somewhere etc.

So

- prami

- Loves.

means the same as

- zo'e prami zo'e

- Someone loves someone.

So in other words.

- bridi = optionally one or more sumti + one selbri

or in English

- phrase = optionally one or more nouns + one verb relation of the phrase.

The verb relation (selbri) describes relationships of nouns. It can be represented as a single verb word (brivla) or as a compound verb (tanru).

Here are some examples of nouns and verb relations.

- ti ladru

- This is milk.

Here ti is a noun and ladru is the verb relation consisting of one verb word.

- lo mlatu cu sutra pinxe

- A cat quickly drinks.

Here lo mlatu is a noun (sumti) and the compound verb sutra pinxe works as the verb relation (selbri).

tanru, or compound verbs consist of two or move verb words. Each left verb word is called seltau compared to the right one called tertau. tanru has the place structure of the most rightward tertau:

- tu sutra bajra bruna mi

That is a quickly running brother of me- That is my quickly running brother.

So the place structure is the same as of bruna alone.

Verbs and particles

All Lojban words are divided into two groups: verbs (brivla) and particles (cmavo).

Verbs are divided into 4 groups by their form:

- gismu, or root-words are main building blocks of Lojban vocabulary. gismu are easy to recognise, because they always have five letters, in the form

- CVCCV — e.g. ladru, gismu, sumti, or

- CCVCV — e.g. mlatu, cmene, bridi, klama

- where C=consonant and V=vowel.

- Verbs in the following forms are created when there is no appropriate verb in gismu list:

- lujvo, or compound words. They are created from short building blocks (called rafsi) used for mnemonic purposes.

- Examples are: reisku, kargau

- zi'evla, or free words. They are usually created for specific concepts and things like igloo (iglu in Lojban), spaghetti (spageti in Lojban).

- cmevla, or name words. They are mostly used to build personal names. You can easily recognize them in a flow of text as being wrapped by one dot from both sides. Besides, if not count dots they always end in a consonant. Examples are: .paris., .robin.

Which of the following Lojban words are:

a. gismu

b. cmevla (remember, they always end in a consonant)

c. neither?

Note: I've left out the full stops in the cmevla — that would make it too easy!

- lojban

- dunda

- praxas

- mi

- cukta

- prenu

- blanu

- ka'e

- dublin

- selbri

Particles (cmavo) are short words like lo, cu, pu, ca, ba, mi, do, ti. They can be divided by their meaning and function into groups that are called selma'o. E.g. pu, ca, ba belong to the group PU. This is just an illustration, there is no need in memorizing the names of selma'o. But it's convenient to memorize them by those groups.

Places for nouns

How do we say You are my friend ?

- do pendo mi

- You are my friend.

You are a friend of me(literally)

And now how do we say My friend is crazy.?

- lo pendo be mi cu fenki

- My friend is crazy.

So when we convert a verb into a noun (pendo - to be a friend into lo pendo - a friend) we can still retain other places of that verb by placing be after it.

By default it attaches the second place (x2). We can attach more places by separating them with bei.

For example:

- mi dunda lo cukta do

- I give the book to you.

- lo cukta - book

And now

- lo dunda be lo cukta bei do

- The grantor of the book to me

- lo dunda be lo cukta bei mi cu pendo mi

- The giver of the book to me is my friend.

- The one who give the book to me is a friend of mine.

Another example:

- bangu - x1 is a language used by x2 to express ideas x3

- la .lojban. cu bangu mi

- Lojban is my language.

Lojban is a language of me.(literally)

How to translate the following phrase?

- I like my language.

The answer is

- mi nelci lo bangu be mi

We can't elide be because lo bangu mi are two independent nouns (well, the second one is a pronoun but it's all the same in Lojban). We also can't use nu because lo nu bangu mi is some event about my language. So lo bangu be mi is a correct solution to the problem.

Using be for not-converted verb words has no effect: mi nelci be do is the same as mi nelci do.

What if I want to attach nouns from several places to a noun? The giver of the apple to you is lo dunda be lo plise be do, right? Nope.

- plise - x1 is an apple of species/variety x2

The second be attaches to the apple, meaning lo plise be do - The apple of the strain of you, which makes no sense. In order to string several nouns to a noun, the all the ones following the first must be bound with bei.

There are also ways to loosely associate a noun with another. pe and ne for restrictive and non-restrictive association. Actually, lo bangu pe mi is a better translation of my language, since this phrase, like the English, is vague as to how the two are associated with each other. pe and ne are used as loose association only, like saying my chair about a chair which you sit on. It's not really yours, but has something to do with you. A more intimate connection can be established with po, which makes the association unique and binding to a person, as in my car for a car that you actually own. The last kind of associator is po'e, which makes a so-called "inalienable" bond between nouns, meaning that the bond is innate between the two nouns. Some examples could be my mother, my arm or my home country; none of these "possesions" can be lost (even if you saw off your arm, it's still your arm), and are therefore inalienable. Almost all of the times a po'e is appropriate, though, the x2 of the verb contains the one to which the x1 is connected, so be is better.

- ne - non-restrictive relative phrase. "which is associated with..."

- pe - restrictive relative phrase. "which is associated with..."

- po - possesive relative phrase. "which is specific to..."

- po'e - inalienable relative phrase. "which belongs to..."

A very useful construct to know is lo {noun} {verb}. this is equivalent to lo {verb} pe {noun}. For example, lo mi gerku is equivalent to lo gerku pe mi.

Another common way of saying my is transforming pronouns and personal names COVERED??? into verbs using the particle me.

E.g. mi is pronoun by itself. We need to turn it into a verb word.

me turns nouns (as well as pronouns and personal names) into verbs. After getting me mi we can readily use it in compound verbs.

- me mi verba - my child.

- tu me mi verba – this is my child.

lo and me have opposite functions.

Passive voice. Nouns from other places, two words from one

dunda means to give (something).

- do dunda ti

- You give this.

You can choose another style and say

- ti se dunda do

- This is given by you.

do dunda ti means exactly the same as ti se dunda do! The difference is solely in style.

You may want to change things around for different emphasis (people tend to mention the more important things in a sentence first). So the following pairs mean the same thing:

- mi viska do

- I see you.

- do se viska mi

- You are seen by me.

- lonu mi tadni la .lojban. cu xamgu mi

- My study of Lojban is good for me.

- mi se xamgu lo nu mi tadni la .lojban.

- For me it's good to study Lojban.

As we remember, when we add lo in front of a verb it becomes a noun. So lo dunda means something(s) which could fit in the first place of dunda.

- lo dunda

- a giver, a donor, a donator

As dunda actually means not just to give but to donate (something) it defines that the noun after it (the second argument) is actually something that is given.

Well, therefore it's a gift.

In Lojban we don't need a separate word for a gift. It's much easier

If a verb word has the second argument you can prefix it with se and it will refer to the second place of that verb:

It's just

- lo se dunda

- something that is given

- gift

For the ease of understanding and memorising predicate words prefixed with se are put into the dictionary as well together with their definitions although you can easily figure out their meaning yourself.

So you don't have to memorise numerous interconnected words. Lojban is much easier.

We save a lot of words because of such clever design.

Indeed, we can't imagine a gift without implying that someone gave it or will give it. When phenomena are connected Lojban reflects this.

Changing other places in verb relations

se is part of a series of particles which go, in alphabetical order, se, te, ve, xe. Like a lot of these series, the first one (se) is used a lot more than the others, but sometimes the others are useful.

- se changes round the first and second places

- te changes round the first and third places

- ve, the first and fourth, and

- xe, the first and fifth.

- mi'ai vitke do lo zdani

- You visit me at home.

- lo zdani cu te vitke do mi'ai

- Home is where you are being visited by us.

The mi'ai has now moved to a less conspicuous place in the sentence, and so can now be dropped out without being missed if we are too lazy to specify who exactly visit you:

- lo zdani cu te vitke do

- Home is where you are being visited.

In fact place conversion is often used when we want to get rid of places like this.

- mi tugni do zo'e lo cukta

- mi tugni do fo lo cukta

- I agree with you [that something is true] about the book.

- lo cukta cu ve tugni

- The book is what [I] agree about.

- lo prenu cu klama zo'e zo'e zo'e lo trene

- lo prenu cu klama fu lo trene

- The person goes somewhere, from somewhere, via somewhere, by train.

- lo trene cu xe klama

- [Someone] goes by train.

- Literally,

By a train is gone. - A train is a vehicle.

The more extreme conversions like ve and xe are rarely used, partly because most verb words only have two or three places, and partly because even with four- or five-place verbs, the less-used places are less needed in ordinary speech.

Convert the following sentences so that the underlined noun comes first. Miss out any unimportant places.

- zo'e fengu lonu jamna

- ti xatra mi la .djang.

- zo'e xlura mi lonu cliva lo gugde kei loi jdini

- lo prenu cu tavla zo'e zo'e la .lojban.

- lo prenu cu dunda lo cukta mi

Rearrange these Lojban sentences so that the main selbri in each sentence is converted to having se. Don't forget to use cu if you need to! For example, mi viska do → do se viska mi

- mi prami la .meilis.

- lo mlatu cu catra lo jipci

- la .mari,as. cu vecnu lo mlatu

- la .mari,as. cu dunda la .iulias. la .klaudias.

- la .mari,as. cu vecnu zo'e la .tim.

- la .fits.djerald. cu fanva fi lo glico

- klama la .bast,n. fu lo karce

- li ze tcika lonu tivni la .SEsamis.strit. (Leave the phrase with tivni alone).

- la .klaudias. cu nelci lonu zo'e vecnu loi kabri la .iulias. (Convert the phrase with vecnu as well as the phrase with nelci).

- la .tim. cu nelci lonu li paso tcika lonu la .meiris. cu cliva (Convert all three selbri).

Getting nouns from other places

Similarly to our example with lo se dunda (a gift) we can use te, ve, xe to get more words from other places of verbs.

- lo prenu cu dunda lo cukta mi

- A person gives a book to me.

lo prenu can also be lo dunda - the giver. But what about the noun describing mi and lo cukta? Well, you probably guessed.

- mi te dunda lo cukta

This means that mi can be lo te dunda - the recipient. In the same way, lo cukta can be lo se dunda - the gift or the thing given. So if we want to make a really obvious sentence, we can say

- lo dunda cu dunda lo se dunda lo te dunda

- The donor gives the gift to the recipient.

The giver gives the given-thing to the person-to-whom-it-is-given

Guessing place structure

Places of verbs might sometimes sound hard to remember. But let's not worry — we don't have to memorise all of them. In fact nobody does!. There are a few cases where it's worth learning the place structure to avoid misunderstanding, but usually you can guess place structures using context and a few rules of thumb.

- The first place is often the person or thing who does something or is something.

- If someone or something has something done to them, he/she/it is usually in the second place.

- to places (destinations) nearly always come before from places (origins).

- Less-used places come towards the end. These tend to be things like ‘by standard’, ‘by means’ or ‘made of’.

The general idea is that the places which are most likely to be filled come first. You don't have to use all the available places, and any unfilled places at the end are simply missed out.

Try to guess the place structure of the following gismu. You probably won't get them all, but you should be able to guess the most important ones. Think of what needs to be in the sentence for it to make sense, then add anything you think would be useful. For example, with klama, you need to know who's coming and going, and although you could in theory say Julie goes, it would be pretty meaningless if you didn't add where she goes to. Where she starts her journey, the route she takes and what transport she uses are progressively less important, so they occupy the third, fourth and fifth places.

- karce – car

- nelci – like, is fond of

- cmene – name

- sutra – fast, quick

- crino – green

- sisti – stop, cease

- prenu – person

- cmima – member, belongs to

- barda – big

- cusku – say, express

- tavla – talk, chat

Add cu to the following Lojban sentences where necessary, then work out what they mean. For example, for lo klama ninmu to make sence as a sentence, you need to add cu: lo klama cu ninmu.

Changing Places

We've seen that if we don't need all the places (and we rarely do), then we can miss out the unnecessary ones at the end of the phrase. We can also miss out the first place if it is obvious (just like in Spanish). However, it sometimes happens that we want places at the end, but not all the ones in the middle. There are a number of ways to get round this problem.

One way is to fill the unnecessary places with zo'e, which means something or someone. So mi klama lo tcadu lo purdi zo'e lo karce tells us that I go to a city from a garden by car, but we're not interested in the route she takes. In fact zo'e is always implied, even if we don't say it. If someone says klama, what they actually mean is

- zo'e klama zo'e zo'e zo'e zo'e

but it would be pretty silly to say all that.

Most people don't want more than one zo'e in a sentence (though there's nothing to stop you using as many as you like).

A more popular way to play around with places is to use the place tags fa, fe, fi, fo and fu - those are particles of the class (selma'o) FA. These mark a noun as being associated with a certain place of the selbri, no matter where it comes in the sentence: fa introduces what would normally be the first place, fe the second place, and so on. For example, in

- mi klama fu lo karce

- I go in the car / I go by car.

fu marks lo karce as the fifth place of klama (the means of transport). Without fu, the sentence would mean Susan goes to the car.

After a place introduced with a place tag, any trailing places follow it in numbering. So in

- mi klama fo lo tcadu lo karce

- I go via the city by car.

lo tcadu is the fourth place of klama, and lo karce is understood as the place following the fourth place — i.e. the fifth place.

With place tags you can also swap places around. For example,

- fe lo cukta cu dunda fi lo nanla

- The book was given to a boy.

(The book — lo cukta — is the second place of dunda, what is given; a boy — lo nanla — is the third place of dunda, the recipient).

Again, you probably don't want to overdo place tags, or you'll end up counting on your fingers (although they're very popular in Lojban poetry — place tags, that is, not fingers).

A final way to change places is conversion, which actually swaps the places round in the selbri — but we'll leave that for another lesson. There are no rules for which method you use, and you can use them in any way you want, so long as the person you're talking to understands.

Reorder the nouns with place tags in these Lojban sentences so that no place tags are necessary, and the nouns appear in their expected places. Insert zo'e where necessary. For example: fi mi pritu fa lo karce - lo karce cu pritu zo'e mi

- fo lo cukta cu cusku fe lo glico fi lo prenu

- fi mi vecnu fa do lo karce

- fu ti fanva fi lo glico fa do

- mi vecnu fo lo rupnu

- fi lo rokci cu kabri

- fi lo banjubu'o fo lo banjubu'o cu tavla fa do

Particles. Interjections

There is a group of particles called interjections, or attitudinal indicators. They express how the speaker feels about something. The most basic ones consist of two vowels, sometimes with an apostrophe in the middle. Here are some of the most useful ones with some examples.

| .a'o | I hope | .a'onai | despair

| ||

| .a'u | interest | a'ucu'i | no interest | a'unai | repulsion

|

| .ai as in high | intent (I'm going to...) | .aicu'i | indecision | ainai | refusal

|

| au as in how | desire | aucu'i | indifference | aunai | reluctance

|

| e'a | permission | e'anai | prohibition

| ||

| e'i | constraint | e'icu'i | independence | e'inai | resist to constraint

|

| e'o | request | e'onai | negative request

| ||

| e'u | suggestion | e'ucu'i | no suggestion | e'unai | warning

|

| ei as in hey | obligation | einai | freedom

| ||

| ia like German Ja | belief | iacu'i | skepticism | ianai | disbelief

|

| i'e | approval | i'ecu'i | non-approval | i'enai | disapproval

|

| ie like yeah | agreement | ienai | disagreement

| ||

| ii | fear (Think of Eeek!) | iicu'i | nervousness | iinai | security

|

| io | respect | ionai | disrespect

| ||

| iu like you | love | iucu'i | no love lost | iunai | hatred

|

| o'u | relaxation | o'ucu'i | composure | o'unai | stress

|

| oi as in boy | complaint/pain | oicu'i | doing OK | oinai | pleasure

|

| u'e | Wow!; wonder | u'enai | commonplace

| ||

| u'i | amusement | u'inai | weariness

| ||

| u'u | I'm sorry!; repentance | u'ucu'i | lack of regret | u'unai | innocence

|

| ua as in waah!, or French quoi | discovery ('Ah, I get it!') | uanai | confusion (I don't get it, Duh...)

| ||

| ue as in question | surprise | uecu'i | no surprise | uenai | expectation

|

| ui like we, or French oui | I'm happy | uinai | I'm unhappy

| ||

| uo as in quote | Voila!; completion | uonai | incompleteness

| ||

| uu | pity | uunai | cruelty

| ||

| je'u | Yes, it's true | je'unai | No, it's false, not true

|

As you can see the emotion is turned into it's opposite by adding nai, so .ui is an interjection of happiness while .uinai means I'm unhappy, and so on. By adding cu'i we create an emotion in the middle. Not all interjections are meaningful with cu'i. One of the most used ones is .a'ucu'i - no interest (while .aunai denotes repulsion).

You can also combine interjections. For example, .iu .uinai would mean I am unhappily in love. In this way you can even create words to express emotions which your native language doesn't have. Another example:

- .ue .ui do jinga

- Oh, you won! I'm so happy!

where jinga = to win.

In this case the victory was unprobable, I'm surprised and happy at the same time.

Another great thing about interjections is that you can attach them next to any noun, pronoun or verb thus expressing your attitude towards that part of the sentence.

- lo mlatu .ue cu pinxe lo ladru

A cat (surprise!) is drinking milk.- A cat (wow, how unexpected!) is drinking milk.

You can as well attach interjections to the right of any verb relation. Or put it in the beginning of any sentence thus changing your attitude to the whole sentence.

- .o'u tu mlatu

(relaxation!) that is a cat.- Oh, that's only a cat.

In this case you probably thought that was something dangerous but it's only a cat so you are saying .o'u.

You can pile several interjections to any part of the sentence. For example,

Using the interjections above (including negatives), what might you say in the following situations?

- You've just realized where you left your keys.

- Someone treads on your toes.

- You're watching a boring film.

- Someone's just told you a funny story.

- You disagree with someone.

- Someone's just taken the last cookie in the jar.

- You really don't like someone.

- You are served a cold, greasy meal.

- Your friend has just failed a test.

- There is a large green beetle crawling towards you.

Forgot to put an interjection in the beginning?

What if you forgot to put an interjection in the beginning of a verb phrase?

- mi jinga

Now you want to add .ui so that it modifies the whole phrase. In

- mi jinga .ui

.ui modifies only the verb jinga.

No problem here. You just add vau in the end and then the interjection that you need.

- mi jinga vau .ui

- vau - a particle. Show that the verb phrase just ended.

Commands

How do we do commands and requests in Lojban?

For example, if I want you to run, I'd probably say:

- Run!

Now the verb for to run is bajra.

How do we do this in Lojban? We can't copy English grammar and just say bajra, since it can just mean the same as zo'e bajra, someone or something runs. It would be too vague. Instead we say

- do ko'oi bajra

do bajra means You run. And ko'oi is an interjection that turns You runю into a command, request, desire, hope or suggestion.

do ko'oi is so useful and frequent in speech that in spoken Lojban it is also common to use a contraction of it, the word ko. It's just a shorter synonym of do ko'oi.

We can put it in any place where we put do transforming it into commands, e.g.

- nelci ko

nelci = to like Template:Talkquote This means something like 'Act so that someone likes you, and sounds pretty odd in English, but you could use it in the sense of Try to make a good impression. Another example is:

- mi dunda lo cifnu ko

- Act so that I give the baby to you.

with the possible meaning Stop playing the piano — I'm going to pass you the baby.

As noted earlier any interjection modifies only the part of the sentence that it follows. Moving ko'oi to another part moves command/request to that part.

You can even have several ko'oi in one sentence.

- do ko'oi kurji do ko'oi

which in short form would be

- ko kurji ko

- [Act so that] you take care of you.

Template:TalkquoteGreen As for ko'oi itself it is mostly used when applying to other pronouns (not do). E.g.

- mi'ai ko'oi klama

- Let's go.

Here ko'oi is applied to the pronoun mi'ai (we) although in ordinary speech it would probably be contracted to just

- ko'oi klama

which is equivalent to

- ko'oi zo'e klama

Imagine that someone says these things to you. What is it that they want you to do?

- ko klama mi

- ko dunda lo cukta mi

- la .izaBEL. cu nelci ko

- ko sutra

- ko ko nelci

Polite requests

As ko'oi is rather vague sometimes we need to be more precise. E.g. often we need to ask polite questions. Foreigners in England often make the mistake of thinking that putting please in front of a command makes it into a polite request, which it doesn't (in English we usually have to make it into a question e.g. Could you open the window?) Fortunately, in Lojban, ‘please’ really is the magic word. Putting the word .e'o before a sentence turns it into a request; e.g.

- .e'o do dunda lo cukta mi

is literally Please give me the book, but is actually more like Could you give me the book, please? (Of course, norms of politeness in English do not necessarily translate into other languages, so it is better in such cases to be safe than sorry).

Modifying interjections

- When we put nai after an interjection it turns it into it's opposite.

- When we put cu'i after an interjection it turns it into the middle attitude.

- When we put dai after an interjection we show listener's attitude.

- .o'adai do jinga - You must be proud since you won

- When we put pei after an interjection it turns it into a question.

- .iepei lo ninmu cu melbi - do you agree the the woman is pretty?

It is possible to use those particles without interjections alone.

- Any verb can be made negative by using nai. Unlike when used in interjections nai after verbs or nouns means not opposite thing but just "no" or "not". So mi nelci nai do means I not-like you, or in other words, I don't like you.

- Any verb can be made middle in it's meaning by using cu'i. So mi nelci cu'i do means As for whether I love or hate you, I'm indifferent to you or in other words, I neither like nor hate you.

- pei not after an interjection asks a general question.

Questions

In English, we make a yes/no question by changing the order of the words (e.g. You are ... - Are you ...) or putting some form of do at the beginning (e.g. Does she smoke?). This seems perfectly natural to someone whose native language is English (or German), but is actually unnecessarily complicated (as any speaker of Chinese or Turkish will tell you). In Lojban we can turn any proposition into a yes/no question by simply putting pei somewhere in the sentence (usually at the beginning.) Some examples:

- pei do nelci lo gerku

- Do you like dogs?

{no need for a question mark}

- pei mi klama

- Am I coming?

- pei crino

- Is it green?

There are two ways to answer these questions. Lojban, like some other languages, does not have words that mean yes or no. One way to answer yes is to repeat the selbri e.g.

- pei do nelci lo gerku

- nelci

As pei is an interjection we can put it after certain parts of the questions shifting the meaning.

Some possible explanations of such shift in emphasis are given in brackets.

- pei do nelci lo gerku

- Do you like dogs?

- do pei nelci lo gerku

- Do YOU like dogs?

- (I thought it was someone else who likes them).

- do nelci pei lo gerku

- Do you LIKE dogs?

- (I thought you were just neutral towards them).

- do nelci lo gerku pei

- Do you like DOGS?

- (I thought you liked cats).

As you can see what is expressed using intonation in English is expressed by moving pei to different parts of the sentence. Note, that the first sentence asks the most generic question without stressing any particular aspect.

Now how to reply to such 'yes/no' questions?

By simply using an appropriate interjection.

- pei do nelci lo gerku

- Do you like dogs?

- je'u

- Yes

True.

or

- je'unai

- no

Not true.

Other often suitable interjections are .ie (I agree) and .ienai (I disagree), pe'i (In my opinion it's true).

Once again you can use .iepei, pe'ipei to ask question but in this case the listener will be forced to use .ie, .iecu'i, .ienai, pe'i etc. when replying.

Content questions

English also has a number of wh- questions — who, what etc. In Lojban we use one word for all of these: ma. This is like an instruction to fill in the missing place. For example:

- do klama ma

- la .london.

- Where are you going?

- London.

- ma klama la .london.

- la .kevin.

- Who's going to London?

- Kevin.

- mi dunda ma do

- lo cukta

- I give what to you? (probably meaning What was it I was supposed to be giving you?)

- The book.

In fact combining prepositions or relative clauses with ma can give us other useful questions:

- ca ma - When? (literally, during what)

- bu'u ma - Where? (literally, at what)

- ma poi prenu - Who? (literally, what that is a person)

- ma poi dacti - What? (about objects) (literally, what that is an object)

- se ja'e ma - Why? (literally, because of what)

mo is like ma, but questions a verb relation, not a noun — it's like English What does x do? or What is x? (remember, Lojban doesn't force you to distinguish between being and doing!) We can see mo as asking someone to describe the relationship between the nouns in the question. For example:

- do mo la .kevin.

You ??? Kevin- What are you to Kevin?

The answer depends on the context. Possible answers to this question are:

- nelci: I like him.

- pendo: I am his friend

- prami: I adore/am in love with him.

- xebni: I hate him.

- fengu: I'm angry with him.

- cinba: I kissed him

We've said that mo can also be a What is ... type of question. The simplest example is tu mo — What is this? You could also ask la .meilis. cu mo, which could mean Who is Mei Li?, What is Mei Li?, What is Mei Li doing? and so on. Again, the answer depends on the context. For example:

- ninmu: She's a woman.

- jungo: She's Chinese.

- pulji: She's a policewoman.

- sanga: She's a singer or She's singing.

- melbi: She's beautiful. (possibly a pun, since this is what meili means in Chinese!)

There are ways to be more specific, but these normally involve a ma-question; for example la .meilis. cu gasnu ma (Mei Li does what?).

There are more question words in Lojban, but pei, ma and mo are enough for most of what you might want to ask.

Choosing a name

If one's name is Bob then we can create a cmevla ourselves that would sound as close as possible to this name, for example .bob.

And then we prefix it with the word la so that it would work just like a noun - la .bob.. The word la is similar to lo but it converts brivla not to a simple noun but to a name (cmene in Lojban).

So the most simple example of using a name would be

- la .bob. cu tcidu

- Bob reads/is reading.

where the verb tcidu means to read.

Well, Bob is lucky because his name goes directly into Lojban without any changes. The same for the name Lojban. Of course it's a cmevla and is written as .lojban.

- la .lojban. cu bangu mi

Lojban is the language used by me.(literally)- Lojban is the language I use.

- I speak Lojban.

However, as you might guess Lojban spelling is quite transparent and therefore there are some rules for adapting names to how they are written in Lojban. This may sound strange — after all, a name is a name — but in fact all languages do this to some extent. For example, English speakers tend to pronounce Jose something like Hozay, and Margaret in Chinese is Magelita. Some sounds just don't exist in some languages, so the first thing you need to do is rewrite the name so that it only contains Lojban sounds, and is spelt in a Lojban way.

Let's take the English name Susan. The two s's are pronounced differently — the second one is actually a z — and the a is not really an a sound, it's the ‘schwa’ we mentioned in the first chapter. So Susan comes out in Lojban as .suzyn..

Two extra full stops (periods) are necessary because if you didn't put those pauses in speech, you might not know where the name started and ended, or in other words where the previous word ended and the next word began. Here are the names that we'll use all over this book:

| .alis. | Alice |

| .bob. | Bob |

| .ian. | Yan or Ian |

| .jasmin. | Jasmine |

| .kevin. | Kevin |

| .meilis. | Mei Li |

And here are some examples of Lojbanizing other names:

| .an. | Anne |

| .axmet. | Ahmet |

| .eduard. | Edward |

| .IBraxim. or .IBra'im. | Ibrahim |

| .odin. | Odin |

You can also put a full stop in between a person's first and last names (though it's not compulsory), so Jim Jones becomes .djim.djonz.

As you can see the last letter of a cmevla must be a consonant. If a name doesn't end in a consonant we usually add use s to the end; so in Lojban, Mary becomes .meris., Joe becomes .djos. and so on. An alternative is to leave out the last vowel, so Mary would become .mer. or .meir..

Other verbs as names

You can use not only cmevla, but also other types of verbs to choose your nickname in Lojban. If you prefer, you can translate your name into Lojban (if you know what it means, of course) or adopt a completely new Lojban identity. {talkquote|Native Americans generally translate their name when speaking English, partly because they have meaningful names, and partly because they don't expect the wasichu to be able to pronounce words in Lakota, Cherokee or whatever!}}

Here are a few examples of Lojbanic names:

- Fish

- finpe - fish in Lojban

- la finpe - your name

- Björn (means bear in Scandinavian)

- cribe - bear in Lojban

- la cribe - your name

- Mei Li (beautiful in Mandarin Chinese)

- melbi - beautiful in Lojban

- la melbi - your name

Introducing yourself. Vocatives

Another type of interjections are vocatives. They function exactly the same as emotional indicators we just discussed but they can have one noun attached after them.

For example,

- mi'e

- self-introduction; identifies speaker.

When do we use it? Watch any film where people don't know each other's language. They start off saying things like "Me Tarzan," which is as good a place to start learning Lojban as any. So here we go.

- mi'e la .robin.

I-am-named Robin- I'm Robin.

And when you address people by name, you usually do so to make it clear who out of a group you are talking to. The word doi is used to show who you're talking to.

- doi la .robert. mi cliva

- Robert, I'm leaving.

- cliva = to leave

Without doi the name might become the first noun of the phrase. doi a bit like English O (as in O ye of little faith) or the Latin vocative (as in Et tu, Brute).

Natural languages don't distinguish between these contexts. We address people in order to manage our conversations: to make someone pay attention to our turn; to butt in before it is our turn; to signal that a conversation is beginning or ending; and so on. We can also do this without using names, but instead by various context cues and all-purpose words. When you think about it, for example, OK does a lot of work for such a small word.

In conversations over two-way radio use them, because it is impossible to talk over each other, or to negotiate whose turn it is to speak through subtle visual cues. A less elaborate vocabulary is in place for IRC, its Internet equivalent. This means that Lojban vocatives look a little like a CB enthusiast's nightmare, because the meanings in the dictionary you see for them come from this more explicit subset of English.

Here are other vocatives:

- mi'e is the word you use to introduce yourself: it's the only vocative followed by the speaker's name, rather than the addressee's. So mi'e la .robin. means I'm Robin or This is Robin speaking.

- co'oi is the greeting/parting word much like Italian ciao: it corresponds to Hello / Bye.

- .o'ai and coi are words for greetings only: it corresponds to Hi, Hello, Good morning, Wazzup?, and whatever else happens to be in vogue.

- coi ro do = Hello all of you (Southern U.S. Hello y'all) is a common way to start a conversation with several people in Lojban. You can also use specific numbers: coi re do would mean Hello two of you or Hello you two (for example, once can start e-mails to their parents with coi re do).

- Conversely, co'o is the farewell word, corresponding to Goodbye, Farewell, Yo Later Dude, and so on. Lojbanists signing off on e-mail often end with something like co'o mi'e .robin. — this is equivalent to putting your name at the end of your email in English as a signature, and translates as Goodbye; I'm Robin.

- ju'i - Hey!, with which you draw someone's attention, and

- fi'i - Welcome! At your service!, with which you offer hospitality or a service. (It's what you say to a visitor; you wouldn't say it over the phone, for instance, unless your addressee is calling from the airport and is on their way over).

- ki'e - Thank you and the appropriate response is not fi'i (You're welcome doesn't mean you're being visited by some guests), but the simple acknowledgement je'e.

- je'e corresponds to Roger! in radio-speak, and right or uh-uh in normal English: it confirms that you've received a message. If you haven't, you say je'enai instead (of course); in normal English, that would be Beg your pardon? or Huh?.

- In case you haven't received the message clearly, you can explicitly ask for the speaker to repeat whatever they said with ke'o.

- Similarly, be'e signals a request to send a message (Hello? Are you there?), and re'i indicates that you are ready to receive a message. It's what you say when you pick up the phone — which in English also happens to be Hello?, but in Italian is Pronto or Ready!.

- mu'o is what you say when you explicitly make it another speaker's turn to speak: it's the Over! of radio.

Other vocatives are not as common:

- When it isn't your turn to speak, but you want to barge in anyway, you can say ta'a — though it probably won't make anyone any happier that you're interrupting.

- pe'u introduces a request, and so is fairly similar to the interjection .e'o although can put the addressee after it:

- pe'u la .robin. ko tavla mi

- Please, Robin, talk to me

- vi'o acknowledges a request, and promises to carry it out: in radio talk this is Wilco!, and in normal English OK or All right, I will (or for that matter, Consider it done!)

- nu'e introduces a promise

- Finally, to close communication (radio's Over and out!), you can use fe'o. (This is what people actually should be putting at the end of their e-mails; but it's not as well-known a word as co'o)

Vocatives take nouns (sumti) after them. However, the rule is that if it's a noun with lo you can drop that lo for brevity so

- coi lo pendo

- Hello, friends!

is the same as

- coi pendo

If you use the vocative on it's own (without a noun after it) and the sentence is not finished yet then you need to separate it from the rest, because the things likeliest to follow the vocative in a sentence could easily be misconstrued as describing your addressee. Use the word do for that. For example,

- coi do la .alis. la .meilis. pu cliva

- Hello! Alice left Mei Li.

Hello you! Alice left Mei Li(literally)- coi la .alis. la .meilis. pu cliva

- Hello, Alice! Ranjeet's just left.

And if you want to put both vocatives and interjections modifying the whole sentence please put interjections first:

- .ui coi do la .alis. la .meilis. pu cliva

- Yay, Hello! Alice left Mei Li.

Note that in the beginning of sentences usually interjections are put before vocatives because

- coi .ui do la .alis. la .meilis. pu cliva

means

- Hello (I'm happy about this greeting) you! Alice left Mei Li.

So an interjection immediately after a vocative modifies that vocative. Similarly, interjection modifies the vocative noun when being put after it:

- coi do .ui la .alis. la .meilis. pu cliva

means

- Hello you (I'm happy about you)! Alice left Mei Li.

Give the Lojban vocatives corresponding to the emphasised words in each of the following sentences. You may need to add nai to your vocatives. Beware of trick questions!

- Jyoti, are you there? - Just a second!

- Come on in, Zhang, make yourself at home! - Much obliged!

- You're coming along, right? - Come again?

- Excuse me, is this seat taken? - Be my guest!

.i

When saying one sentence after another in English we make a pause (it may be short) between them. Oh, this pause. It has so many different meanings in English. Clearly, in Lojban we need to have a better way of understanding where one sentence ends and another begins.

In fact the most precise way of uttering sentences in Lojban would be placing a short word .i in the beginning of each of them.

.i - this word separates sentences

Sometimes when pronouncing words quickly you can't figure out where one sentence ends and the word of the next sentence begins. Therefore it's advised to use the word .i before starting a new sentence.

he and she

So far we've been referring to everybody by name, which can get very repetitive if you want to tell a story, or even string two sentences together. Consider the following:

- la .alis. cu klama lo barja .i la .alis. ze'a pinxe lo vanju .i la .alis. cu zgana lo nanmu .i lo nanmu cu melbi .i lo nanmu cu zgana la .alis.

- Alice goes to the bar. Alice drinks some wine for a while. Alice notices a man. The man is beautiful. The man notices Alice.

It is pretty tedious to have to keep repeating Alice and man. English gets round this problem by using pronouns, like she or he. This works OK in this case, because we have one female and one male in the story so far, but it can get confusing when more characters enter the scene. (It's even more confusing with languages that only have one word for he, she and it, like Turkish or spoken Chinese).

In English we use words "he, she, they" very often. Lojban gives us more possibilities

- The particle ri refers to the last noun used in the discourse.

- The particle ra refers to one of the last nouns used in the discourse.

- We can also use the first letters of last nouns or names, e.g. say "R" instead of "Robin" if we were talking about Robin.

- la .alis. cu sipna lo kumfa pe ri

Alice sleeps-in the of-[repeat last sumti] room.- Alice sleeps in her room.

The ri here is equivalent to repeating the last noun or name, which is la .alis., so it is equivalent to:

- la .alis. cu sipna lo kumfa pe la .alis.

Alice sleeps-in the of-Alice room.- Alice sleeps in Alice's room.

Note that ri does not repeat lo kumfa pe ri (which is also a noun), because ri is inside that noun and therefore that noun is not yet complete when ri appears. This prevents ri from getting entangled in paradoxes of self-reference. (There are plenty of other ways to do that!)

Note also that nouns within other nouns, as in quotations, abstractions, and the like, are counted in the order of their beginnings; thus a lower level noun like la .alis. in that last example is considered to be more recent than a higher level noun that contains it.

Most pronouns are ignored by ri. It is simpler just to repeat these directly:

- mi prami mi

- I love me.

- I love myself.

However,

- the particles ti,ta,tu are picked up by ri, because you might have changed what you are pointing at, so repeating tu may not be effective.

- likewise, ri itself (or rather it's antecedent) can be repeated by a later ri; in fact, a string of ri particles with no other intervening nouns always repeat the same noun:

- la .djan. cu viska lo tricu .i ri se jadni lo jimca pe ri

- John sees the tree. [repeat last] is-adorned-by the of-[repeat last] branch.

- John sees the tree. It is adorned by its branches.

Here the second ri has as antecedent the first ri, which has as antecedent lo tricu. All three refer to the same thing: a tree.

Also a vaguer ra is provided. The particle ra repeats a recently used noun. The use of ra forces the listener to guess at the referent, but makes life easier for the speaker. Can ra refer to the last noun, like ri? The answer is no if ri has also been used. If ri has not been used, then ra might be the last noun. A more reasonable version of the previous example, but one that depends more on context, is:

- lo smuci .i lo forca .i la rik. pilno ra

- A spoon. A fork. Rick uses [some previous thing].

Here the use of ra tells us that something other than la .rik. is the antecedent; lo forca is the nearest noun, so it is probably the antecedent. Similarly, the antecedent of raxire must be something even further back in the utterance than lo forca, and lo smuci is the obvious candidate.

The meaning of ri must be determined every time it is used. Since ra is more vaguely defined, they may well retain the same meaning for a while, but the listener cannot count on this behavior.

The two highlighted sumti in each of the following Lojban sentences refer to the same thing or person. For each, check whether the pronoun you have learned — ???lego'i, ri, ra — can replace the second sumti.

- .i la .alis. cu nelci loi vanju .i la .alis. na nelci loi birje

- .i la .alis. cu viska lo nanmu .i lo nanmu cu dotco

- .i la .alis. cu nelci lonu la .alis. cu klama lo barja

- .i la .alis. cu nelci lo la .alis. cu pendo

- .i lonu la .alis. cu badri cu nandu .i la .alis. cu gleki

- .i lenu la .alis. cu badri cu nandu .i lenu la .alis. cu badri na se zgana

Names of letters in Lojban

Each letter has a name in Lojban.

The following table represents the basic Lojban alphabet:

| ' | a | b | c | d | e |

| .y'y. | .abu | by. | cy. | dy. | .ebu |

| f | g | i | j | k | l |

| fy. | gy. | .ibu | jy. | ky. | ly. |

| m | n | o | p | r | s |

| my. | ny. | .obu | py. | ry. | sy. |

| t | u | v | x | y | z |

| ty. | .ubu | vy. | xy. | .ybu | zy. |

As you can see

- to get the name for a vowel, we add "bu"

- to get the name for a consonant, we add "y"

- the word for ' (apostrophe) is .y'y.

We can spell word using these names. For example, CNN will be cy. ny. ny.

Letters instead of he and she

There is another method of referring to nouns and names previously mentioned in speech.

- la robin cu viska lo mlatu i lo mlatu cu viska nai la robin

- Robin sees a cat. The cat doesn't see Robin.

As the first letter in robin is "r" and the first letter in mlatu is "m" we can use names of letters to refer to nouns that we get from them.

- la robin cu viska lo mlatu i my. viska nai ry.

This means the same.

So if you see a Lojban letter being used as a noun, you take it as referring to the last noun or name whose verb word (robin and mlatu in this case) starts with that letter.

Clearly, this method is more powerful than he or she.

But notice that it can happen that we'd like to refer back to, say, {lo mlatu}, but then before we can do so, another noun or name that starts with "m" appeared in the meantime, so that {my.} can no longer refer to the cat. The only way out is to repeat the entire noun or name, i.e. {lo mlatu}.

Only you decide what's to use in speech: the method with ri and ra or the method with letter names.

Comments and quotes

sei

The particle sei begins an embedded discursive verb phrase. This particle allows us to insert comments about our attitude to what is being said exactly as interjections do except they allow us to add whole phrases as a comment. Example:

- do jinga sei mi gleki

- You won! (I'm happy about that!)

In fact .ui means the same as sei mi gleki so we could just say do jinga .ui.

However, look at this:

- do jinga sei la .frank. cu gleki

- You won! (And Frank is happy about that!)

We can't do that with .ui because .ui always describes the attitude of the one who says it.

The grammar of the verb phrase following sei has an unusual rule: the noun must either precede the verb relation, or must be glued into the verb relation with be and bei:

- la frank. cu prami sei la suzan. cu gleki la .djein.

Let's add brackets to make it more easily readable.

- la frank. cu prami (sei la suzan. cu gleki) la .djein.

- Frank loves (Susan is happy) Jane.

- Frank loves Jane (Susan is happy).

Or we can use be to add a second place for the phrase inside sei.

- do jinga sei manci be mi

- You won! (this amazed me)

Quoting text

sei is also useful for quoting text.

mi prami la .mark. sei ra cusku

I love Mark! - she said.

Quotation marks

It is possible, and sometimes necessary, to refer to lower metalinguistic levels. For example, the English she said in a conversation is metalinguistic. For this purpose, quotations are considered to be at a lower metalinguistic level than the surrounding context (a quoted text cannot refer to the statements of the one who quotes it), whereas parenthetical remarks are considered to be at a higher level than the context.

Lojban works differently from English when it comes to marking she said instead of the quotation.

We make such quotations by placing the word lu before the quote and placing li'u after it.

For example,

- la .djon. cu cusku lu mi prami do li'u

- I say "I love you."

- cusku - x1 expresses/says x2 (quotation) for audience x3 via expressive medium x4

lu and li'u are like ‘quote’ and ‘unquote’ — they put something someone says into a noun.

This sentence literally claims that John said (uttered / wrote) the quoted text. If the central claim is that John made the utterance, as is likely in conversation, this style is the most sensible.

However, in written text which quotes a conversation, you don't want the he said or she said to be considered part of the conversation. If unmarked, it could confuse speakers and listeners what ri or ra refers to. In such cases it's better to use sei.

It's interesting that quotation marks in English are not spoken out. They are only written. Instead while speaking we make a short pause to show the beginning and the end of quotations. Lojban can't be that ambiguous. That's why we use those handy quotation words.

You can also nest quotations, e.g.

- la .djon. pu cusku lu la .djein. pu cusku lu coi li'u mi li'u

- John said "Jane said ‘Hello’ to me."

which is similar to

- la .djon. pu cusku lu la .djein. pu rinsa mi li'u

- John said "Jane greeted me."

Lojban is very careful to distinguish between words for things, and the things themselves. So you can't speak about the phrase "the universe") in the same way you speak about the universe itself. To give a silly example, the phrase lo munje is small, but the universe itself is not. To distinguish between the two in Lojban, you need to use quotation:

- lu lo munje li'u cu cmalu

- ‘The universe’ is small.

- lo munje na cmalu

- The universe is not small.

What are other words related to talking?

- cusku - x1 expresses/says x2 (quotation) for audience x3 via expressive medium x4

- reisku - x1 asks x2 (quotation) for audience x3 via expressive medium x4

- spusku - x1 replies/says answer x2 (quotation) for audience x3 via expressive medium x4

- piksku - x1 makes comment x2 (quotation) for audience x3 via expressive medium x4

As you can see all of those verbs have the same place structure so it's easy to remember them.

- tavla - x1 talks/speaks to x2 about subject x3 in language x4

Note the different place structures of cusku and tavla. With cusku the emphasis is on communication; what is communicated is more important than who it is communicated to. Quotes in e-mails frequently start with do cusku di'e (di'e means ‘the following’) as the Lojban equivalent of You wrote. (ciska - ‘write’ places more emphasis on the physical act of writing). With tavla the emphasis is rather more on the social act of talking: you can tavla about nothing in particular.

Indirect quotations (reported speech)

A phrase like Alice said "Robin said "Hello" to me". can also be expressed in a rather more subtle way:

- la .alis. pu cusku lo se du'u la .robin. pu rinsa ra

Alice past-express the-predicate Robin past-greet her.- Alice said that Robin greeted her.

What is this se du'u? This combination allows us to express indirect speech.

Simple du'u is used in Lojban in some places of verbs instead of nu, e.g.:

- djuno - x1 knows x2 (du'u, fact) about x3 by reasoning x4

- mi djuno lo du'u do stati

- I know that you are smart.

It's not a mistake to use nu instead of du'u but it is recommended to use du'u if the dictionary says du'u should go in that place. But what is the difference between them?

Lojban has different words for that..., depending on what sort of thing is meant.

- If that introduces something that happened, use nu. (Events can be subdivided more finely yet, but for now let's not complicate matters even more than necessary).

- If that introduces something that you think, use du'u. This is how you can guess where to put nu and where to put du'u.

- If that introduces something that you say, use se du'u. But if it's a literal quote use lu ... li'u.

zo - Quoting one word

zo is a quotation marker, just like lu. However, zo quotes only the word immediately after it. This means it does not an unquote word like li'u: we already know where the quotation ends. Thus we save two syllables making our speech more concise.

- zo robin cmene mi

- Robin is my name.

- My name is Robin.

Oh yes, this is how you present yourself in Lojban using your lojbanised name. Of course, if you have a name consisting of more than one verb word then use lu ... li'u.

- lu robin djonson li'u cmene mi

- Robin Johnson is my name.

Another way is to use me. It means one of those that are ...

- mi me la robin djonson

- I'm Robin Johnson.

- ki'a = interjection inquiry: confusion about something said; "whaat?? (confusion), pardon?"

Here is a dialogue.

- mi nelci lo kalci

- ki'a ?

- I like shit.

- Whaat???

- Note: Since zo quotes any word following it — any word — it turns out that zo ki'a doesn't mean zo? Huh? at all, but The word ki'a. To ask zo? Huh?, you'll have to resort to zo zo ki'a.

Translate the following disfunctional dialogue.

- .i zo to to mi ca tavla fo la .lojban toi xamgu lonu tavla fo la .lojban

- .i xamgu ki'a

- ni'o xu do nelci lai loglandias.kontrapositivos.

- .i lai ki'a

- .i mi to je do xu toi gleki lonu te vecnu loi matcrflokati

- .i do tavla lo ba'e cizra