me lu ju'i lobypli li'u 15 moi

For a full list of issues, see zo'ei la'e "lu ju'i lobypli li'u".

Previous issue: me lu ju'i lobypli li'u 14 moi.

Next issue: me lu ju'i lobypli li'u 16 moi.

Number 15 - August-September 1991 Copyright 1991, The Logical Language Group, Inc. 2904 Beau Lane, Fairfax VA 22031 USA (703)385-0273 Permission granted to copy, without charge to recipient, when for purpose of promotion of Loglan/Lojban.

First International Correspondence JL to Become Subscription Journal Lojban List Moves Details Inside, and More.

ju'i lobypli (JL) is the quarterly journal of The Logical Language Group, Inc., known in these pages as la lojbangirz. la lojbangirz. is a non-profit organization formed for the purpose of completing and spreading the logical human language "Lojban - A Realization of Loglan" (commonly called "Lojban"), and informing the community about logical languages in general.

For purposes of terminology, "Lojban" refers to a specific version of a logical human language, the generic language and associated research project having been called "Loglan" since its invention by Dr. James Cooke Brown in 1954. Statements referring to "Loglan/Lojban" refer to both the generic language and to Lojban as a specific instance of that language. The Lojban version of Loglan was created as an alternative because Dr. Brown and his organization claims copyright on everything in his version, including each individual word of the vocabulary. The Lojban vocabulary and grammar and all language definition materials, by contrast, are public domain. Anyone may freely use Lojban for any purpose without permission or royalty. la lojbangirz. believes that such free usage is a necessary condition for an engineered language like Loglan/Lojban to become a true human language, and to succeed in the various goals that have been proposed for its use.

la lojbangirz. is a non-profit organization under Section 501(c)(3) of the U.S. Internal Revenue Code. Your donations (not contributions to your voluntary balance) are tax-deductible on U.S. and most state income taxes. Donors are notified at the end of each year of their total deductible donations.

Page count this issue: 88+2 enclosures ($9.00 North America, $10.80 elsewhere). Press run for this issue of ju'i lobypli: 275. We now have about 620 people on our active mailing list, and 240 more awaiting textbook publication.

Your Mailing Label

Your mailing label reports your current mailing status, and your current voluntary balance including this issue. Please notify us of changes in your activity/interest level. Balances reflect contributions received thru 31 August 1991. Mailing codes (and approximate balance needs) are:

Activity/Interest Level: Highest Package Received (Price Each) Other flags: B - Observer 0 - Introductory Materials ($5) JL JL Subscription ($25/yr) C - Active Supporter 1 - Word Lists and Language Description ($15) LK LK Subscription ($5/yr) D - Lojban Student 2 - Language Design Information ($10) R Review Copy (no charge) E - Lojban Practitioner 3 - Draft Teaching Materials ($30) UP Automatic Updates (>$20)

Please keep us informed of changes in your mailing address, and US subscribers are asked to provide ZIP+4 codes whenever you know them.

Contents of This Issue

Important: Due to financial constraints, ju'i lobypli will be fully converting to a subscription basis over the next few issues. Be sure to read the financial news section if you wish to keep receiving ju'i lobypli.

We got a lot accomplished in the months leading up to LogFest, and several major decisions were made at that meeting. See the news section.

la lojbangirz. has made its first research proposal, to the U. S. defense agency DARPA, and also has attended its first linguistics conference. See the news section.

This issue contains a lot of material derived from the Lojban List computer mailing list on the Internet. Nearly all such material has been edited, revised, and corrected from the original. Included are discussions of grammar points, some more on Lojban and linguistics, and a LOT of Lojban text. I have Lojban text material from over a dozen people to choose from for this issue, and it is tough to choose. Some will be saved for JL16.

Table of Contents

News

Finances ---3

Logfest 91 ---5

Lojban List Moves / Electronic Distribution Policy ---7

Language Development Activities ---8

Using the Language --10

Research and Linguistics --11

Products Status, Prices, and Ordering --12

International News --15

Publicity; News From the Institute --16

New Loglans --17

le lojbo se ciska --18, 26, 42, 47, 57, 65

Is Lojban Scientifically Interesting? --20

Summary of gismu/rafsi Official Changes --23

Cleft Place Structures and sumti-Raising --32

Versions of the Theory of Linguistic Relativity --42

On Loglan and Lojban Elidables --47

A History and Description of le'avla in Loglan and Lojban --50

The Culture gismu Revisited: Cultural Neutrality and the gismu

List --53

Grammar Notes: On Observatives; Predications and Identities --61

How to Say It - A New Regular? Feature --63

Translations of le lojbo se ciska --79

Computer Net Information

Via Usenet/UUCP/Internet, you can send messages and text files (including things for JL publication) to la lojbangirz./Bob at: lojbab@grebyn.com (This is a new address and supersedes the prior "snark" address.)

You can also join the Lojban List mailing list (currently around 80 subscribers). Send a single line message (automatically processed) containing only:

"subscribe lojban yourfirstname yourlastname"

to:

listserv@cuvmb.cc.columbia.edu

If you have problems needing human intervention, send to:

lojban-list-request@snark.thyrsus.com

Send traffic for the mailing list to:

lojban@cuvmb.cc.columbia.edu

Please keep us informed if your network mailing address changes.

Compuserve subscribers can also participate. Precede any of the above addresses with INTERNET: and use your normal Compuserve mail facility. If you want to participate on Lojban List, you should be prepared to read your mail at least every couple of days; otherwise your mailbox fills up and you are dropped from the mailing-list. FIDOnet subscribers can also participate, although the connection is not especially robust. Write to us for details if you don't know how to access the Internet network.

Whether you wish to participate in the news-group or not, it is useful for us to know your Compuserve or Usenet/Internet address.

We've been requested to more explicitly identify people who are referred to by initials in JL, and will regularly do so in this spot, immediately before the news section. Note that 'Athelstan' is that person's real name, used in his public life, and is not a pseudonym.

'pc' - Dr. John Parks-Clifford, Professor of Logic and Philosophy at the University of Missouri - St. Louis and Vice-President of la lojbangirz.; he is usually addressed as 'pc' by the community.

'Bob', 'lojbab' - Bob LeChevalier - President of la lojbangirz., and editor of ju'i lobypli and le lojbo karni.

'Nora' - Nora LeChevalier - Secretary/Treasurer of la lojbangirz., Bob's wife, author of LogFlash.

'JCB', 'Dr. Brown'- Dr. James Cooke Brown, inventor of the language, and founder of the Loglan project.

'The Institute', 'TLI' - The Loglan Institute, Inc., JCB's organization for spreading his version of Loglan, which we call 'Institute Loglan'.

'Loglan' - This refers to the generic language or language project, of which 'Lojban' is the most successful version, and Institute Loglan another. 'Loglan/Lojban' is used in discussions about Lojban where we wish to make it particularly clear that the statement applies to the generic language as well.

News

Finances

We may have gotten momentarily overconfident in JL14, after raising a nice amount of money with our fund-raising letter last fall. Unfortunately, since that fund-raiser, income has been lower than the already depressed levels before the letter. We are hoping that this is due only to the recession, but cannot take chances - we have to pay the bills.

We've found that a high percentage of people specifically ordering material from us contribute money to pay for it. It is ju'i lobypli and le lojbo karni, which we send people without a specific prepaid order, that people do not contribute enough to cover. Our financial tracking system finally improved to the point where we could identify this situation.

Yet ju'i lobypli is what people provide most feedback on, a product that people clearly like.

The answer, it seems, is to put JL on a prepaid, specific order basis. Then, presumably, those of you who want JL will tell us so with your checkbooks and credit cards.

This solution engenders its own new problems. We can presume that not every JL subscriber will subscribe if they have to pay for it in full and in advance. But if we drop significantly below 200 U.S. addressees, we lose our reduced 3rd class bulk rates in postage. This reduction amounts to about $2 per copy, or $400 per issue. So, if by reducing our subscriber list for JL does not save us at least $400, we are merely serving less people for the same amount of money. We thus find that there is a gap between about 140 and 200 U.S. subscribers where we lose as much or more money than when we send to additional people who are not paying. We suspect that going to a prepaid subscription basis will put us in the middle of that interval.

Going to a fully paid basis also makes it more difficult for students, people out-of-work, and low-income Lojbanists to get JL. Yet these subscribers are among our most productive volunteers, and have been more likely to spend the time and effort to start learning Lojban. Non-U.S subscribers are also hurt, having a higher price to pay, but often having a lower income because of their country's economy.

Finally, reducing our subscriber list reduces our outreach - our ability to attract new people and get them involved in learning and using Lojban. People who buy our products often learn about them through seeing how others use them productively in JL.

Fortunately, there is one option that may eliminate the bubble. In going to prepaid subscriptions, we may be able to become a 'legitimate' periodical qualifying for U.S. Second Class (Periodical) postage rates. Second Class doesn't require the 200 minimum mailing that our current bulk rate permit does, has even lower rates per piece, and offers faster and more certain delivery than bulk rate mailings.

However, to establish legitimacy, we have to prove that our readers WANT to receive our publication. We can prove this either with formal audit procedures (which we cannot afford), or through having on file explicit requests from each of our subscribers. The latter must be signed and dated, or we must have other proof that the request is bona fide (such as electronic mail headers and addresses). The postal service will audit us at least once a year, and they check carefully.

A side benefit/penalty (depending on whether you are the reader or the editor) is that 2nd class periodicals MUST be published regularly, and at least quarterly, so that JL would be coming out every 3 months with no slips like we've been making lately.

A final factor is that it costs $275 just to apply for a 2nd class permit, so we must have all of our procedures in place BEFORE we apply.

We haven't decided for sure to go to 2nd class mailing - the rigor may be more than we can handle with one full-time worker, me, who has other things to do besides publish JL. But we are going to start jumping through the hoops and see whether we could do so if it proves financially necessary.

Thus, at LogFest 91, we decided on the following steps:

1. JL will be converted to a prepaid subscription basis over a period of around a year. If this means that we lose bulk rate, so be it. Price will be $20- $25/year, payable in advance. People with negative balances will be cut off (switched to le lojbo karni), unless supported either by volunteer credits (see below) or by direct donation by another person.

2. The first step will be a fund-raiser and direct-mail announcement of the new policy in the next month or two. Every subscriber to JL will be sent a form to be signed and returned indicating that you want to receive JL, and a signature line will be added to our order form. If not signed and returned and you have a negative balance, you will be dropped as a JL subscriber, but will receive LK instead. If you have a positive balance, we still need you to return the form to qualify for 2nd class mailing.

3. Thereafter, the negative balance cutoff for JL subscribers will be raised each issue, and people not making the cut will be dropped to an LK subscription. We will give people a one issue advance notice of cutoff. For those with very negative balances, you will be able to avoid the cutoff by explicitly subscribing and sending a signed, paid order for JL.

There will be no exceptions. Some of you with very negative balances may wish to decide what you want your status to be, and possibly to negotiate with someone or with us to continue to receive issues. If you have done things for us, including active participation on Lojban List such that we use your material in JL, you can possibly negotiate delayed payment or a partial amount to be paid to zero out your balance. We ask however that for those who can afford to, you pay most or all of your balances off so that we can help out others who cannot.

We do not intend to drop LK subscribers until the books are done, except upon request. It isn't feasible to put LK on a subscription basis, because the response rate to our mailings is so low.

4. Given the cutback, we hope that our financial condition improves to the point that we have a surplus. If so, the following plan will aid the ones who cannot pay for subscriptions and other materials.

A 'volunteer credit' donation fund will be set up. People who donate can specify donations for general expenses, or specifically for this fund. In addition, a specific portion of any excess revenues (profits) will be put in this fund.

A committee will accept recommendations of people who have contributed in a wide variety of ways from commentary on JL, learning the language, participation on Lojban List, recruiting, overseas activities. They will also get a list from me each issue of people whose balance is less than the subscription cutoff, along with notes on any special circumstances that might allow them to be retained as JL subscribers. The committee will allocate the funds among the possible recipients, so as to allow the maximum number to be retained as JL subscribers.

5. We will seek direct donations of larger amounts of money from companies, especially from computer companies who might profit by the positive image of supporting non-profit scientific and educational research with computer applications. We are asking ALL subscribers associated with a company who might be willing to help support us, and who either have some influence in such decisions, or know who we should contact to request such assistance in your company, to let us know. We will also be directly seeking out ideas and information from a couple of you whom people have recommended that we specifically ask.

We are seeking donations, probably in the $1000-$15000 range, to support specific or general research projects in Lojban applications, and also to support publication of the textbook and dictionary in amounts large enough to keep the price down and allow wide distribution. Specifically from companies that manufacture and sell computers, we also are seeking unrestricted donations of one or two small machines. Unrestricted donation means that we could use or sell the machine - selling it to get money for support or using it for research purposes. Two machines would allow us to sell one and keep one. Donation of machines to la lojbangirz. apparently benefits such companies more than direct cash donations. Again, ideas are welcome in this area.

One such donation will greatly ease our month to month financial pressure. A larger donation or more smaller ones would allow us to make intelligent financial decisions on how to complete our projects and to get serious research started, without the distorting effect of living hand-to-mouth. Please help if you can.

6. We plan to establish a 'Sustaining Membership' similar to other non-profit organizations. Probably costing $50/year, the benefits will be minimal - perhaps acknowledgement in our books, periodicals, and our annual reports, perhaps a 10% or 20% discount on purchases, and higher priority on orders and services. The main 'benefit' will be knowing you are helping make Lojban a success. Details will be announced.

7. Finally, we have gotten a local computer network account which will significantly cut la lojbangirz.'s phone bill.

We believe these steps will be more than sufficient to right our tottering finances. We've made a lot of progress so far, but as we continue to rapidly grow, it is easy to lose control. la lojbangirz. is now far larger than I can financially support by myself.

As a business, we need a safety margin so that financial crisis is not always knocking at the door. And if we have to worry less about finances, that means all the more effort that can be put towards writing books and software and otherwise making sure Lojban continues to grow.

LogFest 91

Logfest 91, the annual gathering for celebration of Lojban, started Thursday night, June 20, with the arrival of the first three visitors, even though no organized activities (other than getting ready) were scheduled for Friday. As happens when a good group of Lojbanists gets together, Friday was filled with a variety of lively and interesting discussions (not limited to Lojban). As people arrived, the discussions got livelier, and a bit more serious.

On Friday night, we turned to discussion of the financial situation, and a related matter - the distribution of Lojban materials electronically (via the computer networks). Such distribution helps our costs by reducing postage, and offers the potential of more rapidly expanding the Lojban community, but with a likely loss of income since many people who receive materials electronically will not contribute to the costs of those materials.

The discussion ran all night, and was heated at times. The result, though, was a workable policy that attendees were satisfied with. This new policy is discussed below.

On Saturday, after a slow start due to late sleepers, we started doing 'serious' Lojban. We had prepared for a couple of dozen different kinds of activities, so as to be ready for a range of Lojban experience and interests. This year, attendees were almost all active students who knew enough vocabulary and grammar for us to undertake intermediate activities.

One activity that proved moderately successful was translating aphorisms. People seem much more comfortable trying to translate single sentences both from English to Lojban and vice versa, than with longer texts. Thus, every participant got a random aphorism out of a box (we pregraded the aphorisms by grammatical difficulty, so people chose a line they had a reasonable chance to translate), and worked on a translation to Lojban. More experienced Lojbanists aided the less skilled ones. Then each person presented her/his translation to the group as a whole, who then tried to figure out what it meant. In general, everyone successfully understood others' translations, using their word lists.

A weakness of the activity was the size of the group. With over a dozen participants, it took a long time to go through all translations. We know next time we have that many people to divide into groups, so that things move quicker. Still, everyone learned a lot, and many were surprised at how easily and well they could understand the translations. You can try the activity yourself - aphorisms in both English and Lojban will be found in le lojbo se ciska this issue.

Less intense was a discussion on making tanru and lujvo. We've tried this before, but working at the level of individual words gets people bogged down in the semantics of English. In this case, working on lujvo for the English word "tyranny", we ended up with over a dozen tanru, each with its own subtle distinction in meaning, and no real agreement on a 'best' one. My own opinion is that there is no 'best' lujvo for any given English concept, because you will choose a different emphasis depending on the context. This exercise, always educational but always somewhat of a failure, reminds us that Lojban and English are very different languages.

There were other activities on Saturday, but the primary focus outside of the above activities was group discussion and socializing. Art Protin and David Twery, visiting from New Jersey and the Philadelphia area respectively met local Lojbanist Sylvia Rutiser, and agreed to start writing Lojban letters to each other; there is now good hope that there will come to be active Lojban social/study groups in those two areas. Art and David also promised that every once in a while they would pile into the car and drive to the DC area for an informal Lojban social get together.

Sunday was dominated by the annual meeting of la lojbangirz., which started at 10:30 AM. That meeting recessed for lunch, but ran until 5 PM as we wrestled with financial issues and priorities for the coming year. A lot of decisions were made, and even more than previous years, I think people were both satisfied with the result and convinced that everyone had a meaningful voice in the process. Since the latter was a major reason for forming la lojbangirz., these long meetings are worthwhile.

We are taking some steps towards speeding up future meetings. We will have more advance notice of agenda items so people can be prepared for discussion before LogFest starts. We will also try to have a Board of Directors meeting perhaps a month before LogFest to weed out issues and ensure group attention to the most important, while expediting routine business. We also hope, of course, that our finances will improve to the point that we no longer have to spend hours debating new strategies.

With such a long meeting, nonvoting Lojbanists tended to drift in and out of the meeting into a variety of discussions and informal activities. By the end of the meeting, a lively game of "la reno preti" (20 Questions) was being played, entirely in Lojban. This proved to be the most successful of the Lojban activities, continuing well-into the evening.

By Monday, only 3 Lojbanists were left. Two stayed until mid-week, with Bob Chassell joining in the regular Tuesday evening conversation group, reporting in Lojban on his touristy explorations of Washington, and leading another round of "la reno preti". One unfortunate problem with a weekend gathering is that so many (especially those from out-of-town) cannot arrive until very late Frday (whereupon they have to sleep half of Saturday in order to recover), and they then have to leave by late afternoon Sunday. Given that the annual meeting so dominates Sunday, this tends to give us less than a day for a variety of activities. Thus the activities portion of LogFest has tended to be only mildly successful.

We work more each year on pre-planning activities, but planning is inherently limited. We never know till people arrive who is coming, what their Lojban skill level is, and what activities they find interesting. Also, as with the aphorism translations, activities that we test out successfully in a weekly conversation session may work quite successfully with 5 or 6 people, but may bog down with a dozen or more participating.

Still, people noted and were pleased by the increasing sophistication of the in-Lojban activities, and the general skill of everyone participating. We still haven't reached the point where Lojban conversations break out spontaneously, but this may happen next year given the rate of improvement in Lojban speakers. More attendees will make this more likely, and improve the variety of activities going on at any one time.

Total attendance was 17, most of whom were there all weekend. 7 were from out-of-town. About half were skilled enough to converse at least minimally in Lojban, although such 'conversations' tended to be only snippets and remarks. 13 attended the business meeting on Sunday. John Cowan was elected to the Board of Directors and Albion Zeglin dropped his Board and voting membership due to lack of time.

LogFest is supposed to be FUN, not all work. A major difference from previous LogFests is that the activities schedule didn't include a mass of technical debates and decisions that had to be made. Of course, since the major Lojban design decisions have been made, only relatively minor questions of style, semantics, and how we teach the language remain to be resolved. These were decided in advance, or in a couple of cases, informally during the gathering (for example, the nest of issues we've called "sumti-raising" - see below - were satisfactorily resolved "in the halls" during LogFest).

Among minor decisions: "?spero" as a culture word for "Esperanto" was voted down, and the baseline of the gismu was reaffirmed; few of the 'old-timers' want even minimal change. "navni" is broadened to include "inert gas" in its meaning. Finally, pending grammar proposals were adopted and the grammar was rebaselined until after the textbook is completed - people are generally satisfied with the grammar for now, and are waiting to see how it is used and taught.

la lojbangirz./Institute split - In accordance with a unanimous vote taken at the time of la lojbangirz.'s original charter in August 1987, when we started "Lojban - The Realization of Loglan", now also known as "Loglan/Lojban" or just "Lojban", la lojbangirz. has made repeated efforts over the last several years to mend the political split with The Loglan Institute, Inc.

Earlier this year, we proposed a settlement that would have remerged the two current versions of Loglan into one. The plan would have guaranteed an honored place for JCB, as well as organizational and possible financial support for the Institute. No response was received.

The Lojban design is essentially complete. Time has run out on making changes to facilitate a merger - we can no longer make significant changes without corresponding impact on those who have learned and will learn Loglan/Lojban. Our version of Loglan is now substantially better than the Institute's, and we have people speaking and writing the language.

As a result of this situation, the LogFest attendees voted that "Expending resources towards reconciliation with JCB or the Institute is not a good use of resources at this time, but we remain open to such reconciliation should their position change in the future." and "There is no longer special authority given to pronouncements of JCB or the Institute about the language."

It is unfortunate that we have had to go to such lengths in our dispute, but we have tried hard and long for an alternative without success. We cannot allow the ill will of one person, even the language inventor, to prevent us from freely using the language he invented. The language belongs to the community now, as it must be to succeed.

We hope that JCB and the Institute will change their position; we then can restore JCB to the position of honor and esteem that he once held among the entire Loglan community.

Electronic Distribution News

Lojban List Moves

A major accomplishment of LogFest was the adoption of a policy for electronic distribution of materials that balances our desire to get these products to the public, thus aiding in the language growth, with our need for income from our publications, and a goal to fairly distribute our services to both computer people and non-computer people.

The essential core of the policy benefits all Lojbanists, regardless of your access to materials: All published "language definition materials" will be placed in the public domain, and will be distributable without restriction, in any medium. These include word lists and the language grammar.

Teaching materials, some draft materials, and all JLs, will be distributable under our retained copyright using a standard license - shown in the distribution policy below.

All materials, except those that we rely on to show a profit to support our other activities (like software and the textbook), will be posted for electronic distribution. Some materials, like ju'i lobypli, will be posted after considerable delay (6 months or more), so that we make a current paid-for copy a valuable service. In addition, the material as posted will generally have minimal formatting for electronic text. Electronic JLs and many other publications will be difficult to read, because standard electronic text uses 80 characters per line, and we use much higher print densities in formatting our publications. As a result, an electronic 'printout' of JL may have sections that will be unreadable without manual editing; la lojbangirz. will not do that editing.

Our point of original distribution will be the 'Planned Languages Server' on the Internet. Over the next few months, as time allows, Bob will prepare materials for distribution. (We will also supply data directly on diskette - current price is $10 per uncompressed diskful, in any of the 4 diskette formats we can support: 5 1/4 and 3 1/2 high and low density MS-DOS.)

For those with Internet access who wish to get materials, send a message containing, on separate lines, "help" and "index lojban" to:

listserv@hebrew.cc.columbia.edu

The Server will reply automatically. The index will identify what files are available - a reading priority should be a 'read-me' file that will describe the files officially put out by la lojbangirz., and their status. The help file will tell you how to request files to be sent to you - generally all you need to do is say:

"send lojban/filename".

On an organized basis, we expect that much of this material will be cross-posted to the Compuserve 'Foreign Language Education' forum by varying Lojbanists with access to both Internet and Compuserve. Lojbanists are welcome to distribute the material electronically in keeping with the policy described below - any restrictions will be noted in the files themselves.

All materials will be released directly by me to Jerry Altzman of the PLS. The read-me file will contain my directory of dates and version numbers of all such releases.

We eventually plan to include in the official directory an MD-4 (tamper-resistant 'message digest' value) for each file so you can verify that material you obtain is authentic. We will also publish a printed MD-4 checksum list separately, and will make available for free a program to determine the MD-4 checksum of any file. There are some hangups in implementing the MD-4 support because the checksum must be calculated on the file as it actually is sent by the Server, which has UNIX-oriented line and file conventions that differ from the ones associated with the MS-DOS version produced by la lojbangirz.

Others are encouraged submit Lojban materials to the Server; we will occasionally check these materials and advise the Server managers (Lojbanists Jerry Altzman and Mark Shoulson) as to which materials we think are useful and current. (We ask that you send us a copy of all such submissions, with a note that you plan to so submit them. Send them either by paper-mail to the la lojbangirz. address, or electronically to:

lojbab@grebyn.com

la lojbangirz. encourages comments on draft materials that are released to PLS.

Jerry Altzman is helping us out in another way. Volume on the Lojban List mailing group has grown so that it was straining list-founder Eric Raymond's network connection. Jerry found room for us on one of the computers he manages, and Lojban List was switched during the last week of August. In addition, the list now uses a more advanced "Listserv" process that allows people to sign up and remove themselves from the list, temporarily suspend receiving messages when overloaded or vacationing, and of course post messages, all without human intervention. See page 2 for details.

Logical Languages Group Policy Electronic Distribution of Materials Approved 23 June 1991 Copyright, 1991 The Logical Language Group, Inc. (la lojbangirz.) 2904 Beau Lane, Fairfax VA 22031-1303 USA Phone (703) 385-0273

All rights reserved. Permission to copy granted subject to your verification that this is the latest version of this document, that your distribution be for the promotion of Lojban, that there is no charge for the product, and that this copyright notice is included intact in the copy.

1) la lojbangirz. publications and materials are hereby divided into three groups:

Group A materials consist of text, and are sold at or near cost.

Group B materials consist of text, and are sold above cost.

Group C materials consist of computer software, and are sold above cost.

This division is independent of the division into Level/Package 0-3 materials, which depends not on cost but on the presumed interest level of the reader.

2) The following are non-exhaustive lists of materials in each group:

Group A: JL and LK issues; draft textbook lessons; word lists; language definition materials; ancillary materials.

Group B: the (as yet unwritten) textbook; the (as yet unwritten) dictionary.

Group C: Logflash for PC and Mac; the la lojbangirz. Lojban Parser (in beta release); lujvo-maker; random sentence generator.

3) la lojbangirz. will provide all materials in Group A for electronic distribution free of charge. All materials, except word lists and other language definition materials, will be copyrighted using a copyright notice essentially similar to the one attached to this draft policy.

4) To assure the integrity of electronically distributed la lojbangirz. materials, every document distributed electronically will bear a message digest value computed using the MD-4 algorithm, source code for which is publicly available.

5) la lojbangirz. will make available, free of charge, a list of the MD-4 message digest values for all materials released in electronic distribution. la lojbangirz. will also provide a program to compute message digest values, free of charge with the purchase of Group C materials, subject to technical limitations.

6) la lojbangirz. intends to use the Planned Languages Server as the primary distribution medium on the Internet. Other distribution media on the same or other networks may be established at la lojbangirz.'s discretion.

7) Materials in Group B and Group C will not be distributed electronically. Group C materials in object form will be distributed on diskette and whatever other media are technically available to la lojbangirz. (currently, none).

8) Source code to Group C software will be made available on diskette or other media to persons who sign a non-disclosure agreement with la lojbangirz., at a cost equal to the cost of the Group C software in object form.

9) This policy becomes effective when ratified by la lojbangirz.'s official bodies. (it has been.) It may be altered at any time by la lojbangirz.

Language Development Activities

Vocabulary - Many minor vocabulary-polishing activities occurred since last issue. 20 gismu proposed and approved last year were finally created using the 6-language algorithm. rafsi were assigned to as many of these as possible, and the cmavo list was examined to see how many cmavo that might be useful in lujvo could be assigned rafsi. The revised rafsi have been released in an updated list - see the products news below. The new gismu and the changes to the rafsi list are in the features section of this issue.

The cmavo list has also been updated - reflecting the grammar and usage developments of the last year. Extended definitions, up to 96 characters long, are incorporated into the new list. The cmavo list update will be released at approximately the same time as JL16 in October, along with the Logflash 3 cmavo instruction software and other materials, giving time for last minute reviews.

The gismu place structure revision has been idling since last fall. This project was intended to produce 96-character extended and clarified place structures/definitions for each gismu, thus providing clearer information for those learning and using the words, and allowing the new list to be used as input for the updated LogFlash 1, now scheduled for October release.

The place structure review will almost certainly not be completed before that October release because of its relatively low priority, so we have decided that a version close to the present working list will be released in October at the time LogFlash is updated, replacing the current list. The new list will become the official public domain language definition list upon release, and we will recommend that people studying or using the language start using that list as soon as possible.

A last minute proposal assigns rafsi to fo'a, fo'e and fo'i (selma'o KOhA). These assigned to names with du or goi plus several other cmavo rafsi (mi, do, vi, va, vu, ti, ta, tu) can be used along with names to allow more abbreviated expressions of cultures not included in the gismu list. e.g. fo'e du la suomis (Finland). .i mi cilre lo fo'enselsanga. (I learn a Finnish song.) Since the most useful culture words are those for 'my' culture and 'your' culture, "mi" and "do" will be likely to be used in this way.

The last paragraph uses the word "selma'o", which may be unfamiliar. We have adopted this lujvo for what we have previously called a "lexeme". The lujvo is based on the second place of "cmavo", which is the grammatical role of the cmavo. The things we are calling "selma'o" are the basic grammatical types of cmavo and other words found in Lojban.

(The definition of "selma'o" shows a little of the meaning variation permissible in lujvo, since selma'o BRIVLA and CMENE are not grammatical units of cmavo, although all other selma'o are. The generalized meaning implicit in "selma'o" is acceptable since people learn finely details of word meanings by seeing how they are used, not by some kind of rigorous analysis.)

Grammar - The proposed changes to the grammar printed in JL14 went without a single comment, or even a question. What little feedback we got seemed to indicate that the discussion was too technical for most readers, and that without considerably more discussion and examples, printing the proposals was not worthwhile.

Additional proposals evolved after JL14 was published, finally totalling 28. All but one, the 'sumti-raising' proposal discussed below, passed without comment from Lojban List as well.

Thus, at Logfest, the set of 28 changes was adopted, and the grammar was rebaselined until after the textbook is completed and reviewed. We do not plan to consider any changes until then, and very few are expected to surface, anyway.

Even the 28 changes adopted are quite minor: almost nothing written in the language in the past two years became ungrammatical as a result of changes, and a few things not grammatical became so, since many of the changes were designed to bring the formal description of the grammar more closely aligned with how people actually were using the language.

Indeed, and this seems significant: in the last few months it has become clear that no longer is the language design being driven by language engineers like myself who are trying to figure out how people WILL use the language. Instead, we have a group of people using Lojban, and what they find out in trying to express things in the language has driven many, if not most, of the most recent changes.

The other significant factor in the grammar is that a complete-grammar Lojban parser has finally been completed. Not only does this provide a new standard for what is grammatical in the language, but it serves as a stabilizing force motivating against changes that might render this valuable tool outdated. (The parser is expected to be released some time this fall.)

Semantics and style - A new entry in this discussion, because the Lojban design plan excludes semantics and style being prescribed. However, we have people actively using the language in conversation, translation, and new writings. The questions that come up in actual usage of the language are generally not grammatical ones, but usage questions like "How do you say this?" and "Why doesn't this work?".

One Lojbanist, Nick Nicholas, has made discussion of style his primary theme on Lojban List. He has backed this discussion with the most prolific use of the language after Michael Helsem (whose Lojban poetry is now truly voluminous - he has published a volume of it).

Style and semantic issues that have been raised and discussed on Lojban List are too numerous to mention here. A lengthy discussion of relativistic tenses started the trend last winter. More recently, the primary topics have been the determination of meaning of lujvo (stimulated by Jim Carter's oft-rejected proposal for what he calls "dikyjvo" - regular mandatory rules for building lujvo based on the source gismu place structures), the distinction between abstract and non-abstract sumti values (tied in with the discussion of 'sumti-raising' - see below), the meaning and usage of the various modals in selma'o BAI, and the mass/set/individual distinction in Lojban descriptors.

Other 'old' issues are really semantic ones. Debate has continued on the necessity and value of the cultural gismu and the gismu that represent elements. Most often the debate derives from new people who are not familiar with the reasons why they were included, which include historical reasons as well as the justification of usage. There is considerable fear that these words will lead to cultural biases, fears not shared by Bob and others who have been working on the language longest. We expect that this issue will not be resolved until the dictionary is published, wherein the words for other cultures and elements that did not get assigned gismu will be listed, along with the rules for deriving new words of those kinds as needed. (An article later in this issue discusses cultural gismu.)

One recurring issue that affects the community as a whole is the frequency and type of translations presented with Lojban text. We can give no translation, or a block translation for an entire text, or line by line translations which are either colloquial English or word-for-word. The more literal the translation, the less need you have to look up words in words lists. This can be both good and bad: the trade-off is between learning the vocabulary or understanding the grammar. Some people want text they can try to read and be challenged. Others are just trying to get a feel for the language. What do you want? What do you think we should change, if anything, in our Lojban text presentations in JL?

Using the Language

This is the most significant area of news, in my opinion. The number of people actively trying to speak and write in Lojban to communicate with others has exploded. Since JL14, I have received or reviewed extensive text (more than a couple of paragraphs of block text) in Lojban from Bob Chassell, John Cowan, Ivan Derzhanski, Coranth D'Gryphon, Michael Helsem, Rory Hinnen, Nick Nicholas, Sylvia Rutiser, Mark Shoulson, David Twery, and written some myself. By comparison, only Jamie Bechtel, John Cowan, Sylvia Rutiser and myself sent in extensive text over the 8 month period between JL13 and JL14.

This is not counting a couple of dozen people who have written letters or sent messages electronically with a sentence or two of understandable and often grammatical text. Several other people have told me that they have written some, or a lot of, Lojban text (in some cases, I am waiting to see before believing; the amounts claimed seem incredible).

Michael Helsem has collected several of his Lojban poems, made corrections, and published them in an artistically decorated cover - copies were given to every LogFest attendee. There are still some Lojban errors in the book, but if you like poetry, the English versions will have value and the enormous volume of Lojban may inspire you, as well as provide ideas on what works and what fails to communicate in Lojban text. We have several copies left of this 'first Lojban book', which we will send free upon request to anyone making a prepaid order over $20, or for postage costs only ($2-$3) otherwise. Michael seeks comments and suggestions from all readers.

John Hodges observes that Michael's publication, even with imperfect Lojban, is a "significant event, symbolically and politically. This is exactly the kind of thing [la lojbangirz.] wanted to make possible by insisting that the language be public domain, and precisely what JCB wanted to prevent by keeping copyright control over the very words of his language. Helsem did not ask permission to publish. You and he took it for granted that it was his right to publish. JCB would deny this. To defend the purity of the language, JCB would insist that Helsem correct his grammar before publishing. (Not to mention, send royalties to JCB.)"

Sylvia Rutiser and Ernest Heramia started an intermittent 'pen-pal' correspondence last winter. Ivan Derzhanski (Bulgaria) and Nick Nicholas (Australia) started the first international correspondence exchange in May. Recently Sylvia, David Twery, and Art Protin started a round-robin letter exchange. I have a list of several others interested in writing letters in Lojban - send us a note with a few sentences (or maybe a self-descriptive paragraph) in Lojban with English translation, and we will try to match you with someone of comparable skill. Give us some indication of how often you would expect to write - one problem we have experienced so far is people prepared to write as often as once a week paired with people who take months to respond.

The amount of Lojban text now being posted on the Lojban List is rather overwhelming at times. Nick Nicholas first got materials from us around the time JL14 was published. He has recently been the most prolific and one of the most skillful among Lojban writers, posting paragraphs of text to Lojban List virtually every week. Noting that Nick is also a full-time student AND one of the leaders of the Australian Esperanto organization, his productivity makes me ashamed of my own (but .ui what inspiration).

Also on the computer network, Jack Bennetto has started a game of "telephone" (you may know this as "whisper down the line", or by another name). Starting with a moderately complex sentence, each successive person translates what he/she receives from English to Lojban or vice versa, and passes the translation to the next person. We've had no reports yet on how well this activity is proceeding.

Weekly Lojban conversation sessions have continued here in the Washington DC area, with anywhere from 3 to 6 attending each session (about 10 people total have participated). The amount of conversation time has dropped a bit, because the group spent time before LogFest planning activities for the gathering. Since LogFest, we have started an intermittent group project - translating the entire board game "Careers" into Lojban in honor of Jim Brown, who invented both the language and the game. (We may seek permission from Parker Brothers Inc., which owns rights to the game, to distribute the game translation to those of you who are interested.)

Not all Lojban text is orderly. Next issue will contain a sampling of the Lojban graffiti that appeared on a wall of Bob and Nora's house (specially prepared to make this non-destructive) during LogFest. One other ongoing activity is the construction of a Lojban traveler's phrase book, after the style of Berlitz.

New Lojbanic activities seem to surface every week or two, and I have no doubt that there will be a new crop of them to report by JL16. Why not let yours be among them?

Research and Linguistics

The Loglan Project is starting to become a real research endeavor again. We have established a presence on several major forums for computer linguistics information exchange, and are making ourselves known to linguists who are researching in areas where Lojban might be relevant. Among these areas are:

- linguistic expression of emotion;

- word compounding;

- predicate deep structure grammars;

- the ISO standards for international character set encodings;

- semiotics;

- representation of abstraction;

- logical expression;

- computational linguistics;

- machine translation;

- abstract system specification language;

- foreign language education.

At least one well-known linguist has expressed interest in Lojban, and we hope to attract many more.

Bob wrote an essay on the linguistic research applications of Lojban for posting to one of these groups. This essay appears later in this issue, slightly edited. A new version of the Lojban brochure will be issued in a couple of months, incorporating some of this material.

Athelstan and Bob attended GURT (The Georgetown University Round Table of Linguistics) this year. GURT is one of the more prestigious linguistics conferences. There were just under 800 attendees. After initially being hesitant for fear of adverse reaction from linguists, on Wednesday we put out about 30 brochures with a short note on Lojban's applicability to linguistics research. They were gone within two hours. On Thursday we put out 110 more, and nearly all were gone when the conference ended at 4PM. We got some great name recognition out of this, even if none of these brochure readers decides to do something about Lojban just yet.

I suspect some will do so eventually. Almost everyone we talked to seemed at least mildly interested in the concept of an artificial language designed for linguistics research, and a couple of researchers thought we had some interesting research angles that they might like to investigate. I would say that Athelstan and I together threw up more questions (usually good from the reaction of the audience and the speaker) than most people, so I'm sure we were noticed.

The primary topic at GURT was foreign language education, but we also attended sessions on natural language processing.

la lojbangirz. is planning to attend at least one and possibly two more linguistics conferences this year.

la lojbangirz. is closer to initiating scientific research using Lojban. The new version of LogFlash contains instrumentation that will allow study of how people learn words, and whether the recognition score algorithm used to build the words has any relevance to their learnability.

More importantly, la lojbangirz. in July prepared and submitted its first research proposal. The proposal (actually a proposal abstract since we did not request a specific dollar amount) was submitted to DARPA (US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency), the primary government funding agency for artificial intelligence and natural language processing research. We didn't win this initial bid, but preparing the proposal stimulated much new activity around here and opened options that look quite promising for the future.

Bidding for research grants is a learning experience. In today's competitive research environment, it may take several proposals to get one grant or contract. The initial proposal not only serves as a basis for further proposals, which are now half written at the start, but every effort we make teaches us more about how to do things better the next time.

For example, since submitting the proposal abstract, John Cowan has been researching and writing up a detailed analysis that shows that Lojban is a superset of the computer language PROLOG, often used in artificial intelligence processing. This means that most, if not all, Lojban sentences could be processed into PROLOG statements and fed into a PROLOG processor. This would greatly reduce the cost and risk of developing a Lojban processor from scratch. (We seek PROLOG experts among the community to review John's work. Let us know you're interested!)

A major plus in our efforts to obtain research funding is John Cowan's completion of a full-language Lojban parser. Still in testing, this parser breaks all Lojban text (including cmavo compounds) down to individual words and parses the results. The ability to parse at the individual word level is a major improvement over the best accomplishments of the Loglan Institute before we started on the Lojban redesign. More importantly, it is better than anything that can be accomplished in processing natural languages.

Of course, our 'advantage' may be a problem with getting DARPA funding. It turns out that having bypassed the worst problems in natural language processing, the problems that we need and want to solve to process Lojban text are quite different than the ones considered on the 'leading edge' of research. We thus are required to write proposals extremely carefully to show how learning to process Lojban text will lead to better processing of natural languages.

We hope to include portions of our proposal in JL16, in order to give our supporters an idea of how we are presenting the language. But also, we welcome suggestions from the community on how to better explain our research approach, and to prove that it is sound. (We also want to hear of any alternate research approaches that we may be missing).

Products Status, Prices, and Ordering

With the decisions described in the finances section, we are making changes in our coding for mailing status. These changes are summarized in the new mailing label coding block on page 1.

Most importantly, we have separated JL and LK subscriptions from the status codes (levels 0, 1, 2, 3, and B). We have also added an automatic update status that is independent of the others, indicating your desire to receive updates and your commitment to keep enough in your balance to pay for them.

Next, we are separating the activity level implied in the level numbers from the encoding of the materials we actually have sent you. As people have moved around in level, or been downgraded, your 'mailing level' no longer tells us what material you have.

The activity level portion of your level will be converted to a letter code indicating your current interest level. The level numbers 0 through 3 will refer to a series of packaged materials that will tell us what we've sent you.

The conversion to letter codes, and their interpretation, is as follows:

(Level B) Observer (old level 0/B)

(Level C) Active Observer/Supporter (old level 1 and 2)

(Level D) Lojban Student (old level 3)

(Level E) Lojban Practitioner (people demonstrating some competency with the language, and actively using it in some regular activity)

('A', in case you are wondering, is used for people dropped from our mailing list, for whom we maintain financial accounts because we've sent materials.)

The difference between old level 0 and old level B has merely been whether you were receiving le lojbo karni or not.

The original difference between old levels 1 and 2 was whether you automatically get updates of materials when they are updated (presumably a level 2 was more active and needed the latest information for active work). Since we went so long without issuing any updates, and have gotten into such a financial morass, the distinction became insignificant.

Then, during the last year, we started sending some additional materials to level 2 people that we don't send to level 1 people, in order to keep the level 1 price down. Thus the original distinction we intended between the two levels was lost, and we are restoring that information as the automated update flag. You will not receive automatic updates unless you keep sufficient balance to pay for them.

These codes will now appear separately on your mailing label, and with the start of paid JL subscriptions, your subscription expiration date/ issue will also appear on your mailing label.

There is increasing interest among Lojbanists in contacting and communicating with others of equivalent skill levels. Right now, Bob makes these evaluations subjectively, but as the numbers of people actually using the language increases, Bob's evaluations become less reliable.

Thus, we are also planning a proficiency code system that will tell us your demonstrated proficiency level at reading, writing, or speaking Lojban. To minimize confusion, we will delay implementing this for about 6 months. Suggestions are welcome, though.

Products and Schedule - This past year has been one of change, of consolidation. We haven't produced many 'new' things; we have been enhancing and refining old ones.

The fruits of that effort are now starting to show up on our order forms. Even more will appear over the next couple of issues. The following is a summary of the current products schedule (as well as the minor releases since last issue):

(Jun 91)

Electronic postings to P.L.S.: Baselined gismu list (old version)

Draft Proposed gismu Place Structure Revisions

Review of Loglan 1 - Draft Long Version

(Aug 91)

Printed:

- Updated rafsi list and lujvo-making guide

(Sep 91)

Printed:

- JL15

- LK15

- Synopsis of Lojban Orthography, Phonology, and Morphology (updated)

- Attitudinal Paper (updated)

- What is Lojban - la lojban. mo Brochure (revised)

- What is Lojban - la lojban. mo Brochure (Esperanto version)

Software:

- Revised Random Sentence Generator

- Revised lujvo-Making Program

Electronic postings to P.L.S.:

- What is Lojban - la lojban. mo Brochure (revised)

- What is Lojban - la lojban. mo Brochure (Esperanto version)

- Overview of Lojban (1991 update)

- lujvo-making guide

- Updated rafsi list

- Re-baselined formal grammar

- E-BNF for re-baselined grammar

- Reply to Arnold Zwicky's review of Loglan 1 (orig. review 1969)

- Revised cmavo list

- Back issues of JL #1-13

- Back issues of LK #8-13

- Summaries of sci.lang discussions of Lojban

- The Lord's Prayer in Lojban (Revised 1991)

- Negation paper

- Lojban Mini-Lesson (Athelstan)

(Oct 91)

Printed:

- Re-baselined formal grammar

- E-BNF for re-baselined grammar

- Lojban Mini-Lesson (Athelstan)

- Revised cmavo list

- Rebaselined gismu list (updated)

Software:

- LogFlash 1 - gismu (Revision 7)

- LogFlash 3 - cmavo (Revision 1)

Electronic postings to P.L.S.:

- Lojban Tense Paper (Cowan)

- Lojban MEX Paper (Cowan)

- Attitudinal Paper (updated)

- Rebaselined gismu list (updated)

- Synopsis of Lojban Orthography, Phonology, and Morphology (updated)

- Lojban and Machine Translation

- Lojban and Esperanto - 16 Rules Comparison and Commentary

- Lojban, Sapir-Whorf and Semiotics

(Nov 91)

Printed:

- JL16

- LK16

Software:

- Lojban Parser (PC and some UNIX versions)

Electronic postings to P.L.S.:

- New Textbook Lesson 1 Draft

- JL14

- LK14

- le'avla-making algorithm and examples (Cowan)

(Dec 91)

Electronic postings to P.L.S.:

- selma'o paper (Cowan)

- Selected list of Lojbanized names

- Revised Draft Lessons 1-6

- A comparison of Lojban and 1989 Institute Loglan (Cowan)

- Glossary of Lojban/linguistic terminology

(Jan 92)

Printed:

- JL17

- LK17

- Lojban Learning Materials (Book)

- Lojban Reference Materials (Book)

Unscheduled But Planned

Printed:

- Lojban Textbook

- Lojban Dictionary

- Lojban Pocket Reference

- Lojban Reader (Book)

- Lojban Phrase Book

Printed and Electronic:

- Lojban gismu Etymologies

Software:

- Logflash 2 - rafsi (Revision 7)

- Hypercard LogFlash/Mac - (Revised and New versions)

- Lojban Adventure Game

Now that we've shown the overall plan, we can explain.

As with all of our schedules, this one should be taken as a plan, not a promise. We are a volunteer organization and the schedule depends on the time availability of specific people. We also are short of money, and the scheduled publications depend heavily on significant numbers of you paying up your balances and putting in additional money to cover these new products.

The true goals are the items listed for next January - two books that will contain all of the teaching and reference materials we have put out, updated to the current language.

In the process of creating those books, all of our current products will be updated to reflect changes in the language or the way we teach it. As each is updated, there will be a heavy emphasis on making it available on the Planned Languages Server. This helps fulfill our obligation and commitment to place the language definition materials in the public domain, enables more people to see detailed design information about Lojban, and of course gives us some last minute feedback on these materials before binding them.

In the process of making these materials available, we will be reviewing them for current accuracy, and will make minor revisions and updates. Some of the printed products will thus not be generally distributed - we won't waste your money (and Bob's time) sending you minor corrections to a publication you may not be using. We will, however, send the latest version on new orders, and inform you in this column about other revisions you may want to know about.

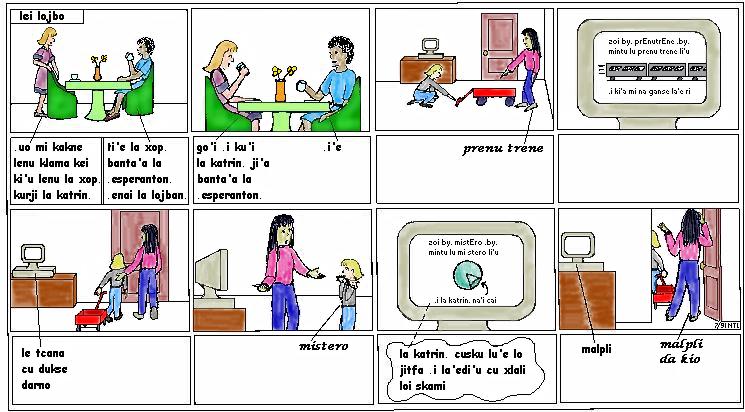

As noted in the discussion of electronic policy above, we will not be rewrite or specially format materials for electronic distribution. Tables and some example texts will suffer the worst; page numbering will be incorrect, and graphics (like Nora's cartoons) will not be presented at all. Some of these materials will thus be of marginal use; consensus is that different people judge usefulness by different standards.

Software updates to all of our software nears completion. In the case of the lujvo-making program and random sentence generator, this is merely an update to accept new data files based on the latest language definition.

As described in JL14, LogFlash, our vocabulary teaching software, is undergoing a major overhaul. The new versions retain the teaching algorithm that has proven so effective, but adds colored screens, user flexibility, and a new learning mode designed to help Lojbanists quickly become familiar with the range of the gismu and cmavo without the time-consuming effort needed to master the lists.

Since the major guideline for this schedule is the earliest practical publication of two books, let us look more closely at what they are and why we are putting them out.

First, these two books may be considered the prototype Lojban textbook and dictionary. The word "prototype" is used because Bob has long had an idea of what a Lojban textbook and dictionary SHOULD be, and these short term products will not be anything like the goal versions.

However, people in the community are in need of books containing materials for studying Lojban, and reference materials needed to use Lojban. Even serious Lojbanists who work with the language a lot are becoming overwhelmed by the volume of materials and updates that la lojbangirz. has issued. Time is being wasted hunting through accumulated ju'i lobypli issues and enclosures, and other materials you have obtained from us, looking for relevant material that has become a bit outdated.

The language design is now firm enough that we can create up-to-date versions of all important materials. By collecting these materials in bound volumes, we give people actively working with the language the tools you need to do so - all in one place.

Bob's work on the textbook revision has dragged on far too long, and the reasons are not going away. Shifting away from long-term targets to short-term goals, he has already picked up in productivity.

The materials being revised and issued electronically (and occasionally in printed form) over the next 6 months will become the contents of the new books. The books will then be assembled out of the revised pieces and published, hopefully, around the beginning of next year.

Under current plans, the learning materials book will contain the 1st lesson of the revised textbook, Lojban mini-lessons by Athelstan and John Hodges, the 6 draft textbook lessons, the negation paper, the attitudinal paper, the old grammar summary, and selected short writings (mostly revised from JL articles) that teach the language. This will be published as a bound book, probably Velo-bound. Total page count will exceed 400 pages. Price will be around $25-$30, depending on the number of advance orders.

The reference manual will contain revised versions of:

- la lojban. mo brochure;

- Overview of Lojban;

- Machine grammar and E-BNF;

- Synopsis of phonology, morphology, and orthography;

- gismu list updated with new place structures, and Roget's Thesaurus codes, and multiple English synonyms where applicable (instead of the English keyword index used now);

- rafsi lists and lujvo-making guide;

- cmavo list with clearer definitions than the current one, possibly with sample sentences for each;

- a glossary of linguistic and Lojban jargon terms;

- a selected list of le'avla borrowings and an algorithm to make more;

- a selected list of Lojbanized names;

- a set of cultural/national words for all countries in the United Nations, and selected other places;

- a selma'o catalog describing the grammar of each word type, with many examples;

- as many sample lujvo as we have time to verify and space to include.

This book will also run about 300-400 pages and be bound. It will also probably cost around $25, depending on orders.

Since we have had an excellent record of recruiting Institute Loglanists who later find out about Lojban, la lojbangirz. is planning a 'guide to Lojban for Institute Loglanists', which may be incorporated in one of the two planned books. This will maximize people's use of the Institute's books that may have been purchased, since much of the material JCB has written applies to Lojban equally as well as the Institute version of the language.

Once the books are out, Bob will then concentrate on producing refined versions while you concentrate on learning and using Lojban. Your efforts will then provide the hundreds of examples needed for the properly completed books.

The only immediately available new product is an updated rafsi list, incorporating the changes listed later in this issue. Also, since people receiving the rafsi in the past have often had no idea how to use it, the section on lujvo-making from the Synopsis has been extracted and heavily revised, and will now be distributed with the rafsi list.

International News

Esperanto brochure - Considerable effort by Paul Francis O'Sullivan, followed up by Mark Shoulson, Nick Nicholas, and David Twery, have led to a complete and up-to-date translation of the la lojban. mo brochure into Esperanto. In addition, Mark is formatting it for a typeset-quality master, and we should have printed copies within a few weeks. The brochure will also be posted electronically on the Planned Languages Server, and possibly on Compuserve.

Large numbers of our readers are Esperantists interested in Lojban. We encourage you to distribute copies of the Esperanto version to other Esperantists. This not only will spread knowledge of Lojban around the world, but it will enhance our position as an artificial language working with the Esperanto community, and not in competition with it. Indeed, we now see Esperanto as one of our primary languages for spreading information about Lojban to other countries.

We don't yet have other materials about Lojban in Esperanto, but we expect that this will change. As more and more Esperantists who also speak English join in with those who translated the brochure, our ability to produce Esperanto translations of our other materials improves.

(We remind our readers that we also have a French translation of the brochure, although it has not been updated yet to reflect new policies and new materials, and is missing the newly added section on Lojban and linguistics research.)

(We are constantly seeking volunteers to translate any of our materials into other languages. Please contact us if interested. Such volunteer work is the type which we qualify for credits in receiving materials when you cannot pay for them.)

Australian Lojban Society - la lojbangirz. has effectively gained an affiliate in Australia. Major, in Perth, and Nick Nicholas, in Melbourne, are attempting to establish and keep contact with all Lojbanists in Australia and New Zealand. In addition, because the cost of mailing overseas is so high, Major is serving as a focal point for la lojbangirz. mailings, and he then redistributes copies to all his correspondents. Nick is becoming one of our most skilled Lojbanists, and can answer most questions about the language.

This benefits la lojbangirz., because we lose money on most overseas mailings even with the 20% surcharge we require. It benefits those who are part of the new group, because it costs less for all of you: Major can produce copies for you and get them to you via local post much cheaper than we can. Major does ask for reimbursing of his expenses, or the group will not be able to grow.

Major and Nick both keep in communication with the rest of la lojbangirz. via electronic mail.

Major's address is:

Major

Box T1680 GPO Perth WA 6001

AUSTRALIA

Nick's address is:

Nick Nicholas

17 Renowden St.

Cheltenham Victoria 3192

AUSTRALIA

It doesn't take a lot of people to make this type of regional group work (there are 7 on our lists in this region of the world, and only 5 are thus far participating). We require that one person is willing to take responsibility to get materials to the others, and also take the financial risk of supporting those who don't pay for materials right away.

We welcome others who would like to try to similarly organize the people of your country and possibly neighboring countries. Already, we have a potential volunteer in Sweden, Christopher Arnold, who hopes to organize and recruit other Lojbanists to join the half dozen of you now in the Scandinavian countries.

Publicity - Bob and Nora's Trip

Bob and Nora travelled to the San Francisco area in late April for a vacation and Lojban promotion trip. We had an opportunity to meet with several Lojbanists, though with a couple we were dogged by an inability to get schedules together. We regret those of you we missed. (One way not to be missed is to make sure we have your telephone number - sometimes plans get made in a big hurry. Specify if the number is unlisted or otherwise not for release to other Lojbanists.)

Bob gave one lecture, to a group of students at St. Mary's College including Dr. Robert Gorsch's class in semiotics that has studied a small Lojban unit (see JL12 for more on this class), and gave two talks combined with mini-lessons to groups of Lojbanists. Dave Cortesi organized and publicized the primary meeting, held in Palo Alto. Donald Simpson organized the other at his house in Albany as a smaller event for those who couldn't get to the other meeting.

A total of around 20 people showed up between the two meetings. Special pleasure was Scott (Layson) Burson's attendance at the Palo Alto meeting. Scott, now inactive in the Loglan community, did the final work to complete the first Loglan parser and the first version of the machine grammar accepted by the Institute.

Jay Stowell arranged to videotape the Palo-Alto mini-lesson. We have considered distributing copies of this, but the cost of videotape duplication is high enough that we want to use a better original (unedited videotapes have a 'home movie' quality about them, and we saw no easy way to turn Jay's tape into a salable product). We are going to try to specially film a mini-lesson, hopefully later this year. Brad Lowry, who does professional video filming, has volunteered to film and edit this mini-lesson.

Some new people attended the Palo Alto meeting, and at least one person signed up as a level 3 Lojban student. All-in-all, the meeting was a success, though we always wish we could have done better at getting information to prospective attendees and helping more people to attend.

Finally, Bob and Nora got together for a brunch with Scott Burson and Doug Landauer, another pioneer in Loglan machine grammar work.

News From the Institute

Legal - Last issue, we thought the legal battles between la lojbangirz. and the Loglan Institute had finally ended. Alas, the day after JL14 went to press, we heard from our lawyer that Jim Brown had informed him of his intent to appeal to the US Court of Appeals.

At this writing, the appeal process is well underway. The Institute has filed its appeals brief and we have responded; we see little chance of the appeal succeeding. We won't go into the issues again at length - anyone interested can contact us for details.

We are hoping for a ruling around the end of the year which firmly closes the door on the legal battle. Meanwhile, we are proceeding in accordance with the decision, using "Loglan" to refer to the generic language of which "Lojban" and what we have been calling "Institute Loglan" are versions.

JCB claims in the new Lognet that our initial challenge was "an harassment designed to strain our resources" and that our suit "is a timewaster once based on the premise that The Institute couldn't or wouldn't be able to respond to their attack."

Our response: No! We hoped that the dispute could be settled by negotiation, but fought at this juncture because we knew our legal position, that 'Loglan' cannot be a 'trademark', was sound, and was important to our making the Loglan project a success. Contrary to what JCB claims, our legal fight started when Jim Brown sent a letter threatening us with legal action (a copy of this letter was included in all issues of JL5); it is unfortunate for all of us that his position on threats was not then what it is today:

JCB reiterates his claims that Bob and Nora split off from the Institute "presumably to accommodate their own entrepreneurial interests", using "the threat of schism to try to make us [change Institute business policies]". He then insists that the two efforts "went their separate ways" because "threats seldom work on human beings".

Our answer: No! Our purpose in starting Lojban was to put Loglan in the hands of the people who had been promised it, had paid for it, and had long assumed that they had the free right to use it as they choose, as "the human use of any language is, of course, in the public domain" (Jim Brown, again, but this time from a 1977 proposal).

JCB also claims that "there were no substantial intellectual differences between me and the proto-Lojbanists".

Response: We consider our commitment to intellectual freedom a substantial difference.

To stop these misstatements of our purpose and goals, and to ensure that there is no further doubt or misconception of our true purpose, we have modified our statements about Loglan and Lojban that appear on page 1 on each issue of ju'i lobypli to more clearly indicate that the free use of Loglan as a human language is the sole reason for the split and our existence.

Actually, of the statements in the new issue of Lognet, those of editor Jim Smith are most ofensive, and are indeed libelous. Mr. Smith accuses la lojbangirz. with the false statements "LLG has been around for just a few years, but they are claiming all of JCB's work since 1955 as their own ... I will not give free advertising to a competitor whose primary technique is plagiarism and whose product lacks any hint of originality." Mr. Smith has received a considerable set of our publications and knows that we claim no work of JCB's as our own. We have formally requested that Mr. Smith issue a retraction and public apology for these uncalled for and unacceptable remarks.

Name of the language - We have been told that some supporters of Jim Brown are offended by our use of "Institute Loglan" for their version of the language. We have asked for an alternative other than the generic name that would satisfy them, but have received no response. We cannot agree to use the generic name "Loglan" only for their version - we need and use the term for our discussion of the evolutionary history of the language that includes Lojban, and in reaching out to people who have heard of Loglan through Robert Heinlein's books or the 1960 Scientific American article, and might not realize that Lojban implements the language described.

The Institute Moves - Shortly before publication, the Institute moved back to San Diego (actually Jim Brown moved - the Institute proper will continue to be incorporated in Florida and hold annual meetings there).

"Careers" Lives - Jim Brown reports that the board game Careers, which he invented, is again on the market. This additional income is bolstering his capability to finance the Institute. He indicates that some money will be earmarked for new Scientific American advertising, which now costs $3500 for one advertisement.

CACM Paper - Since 1982, JCB and others have been writing and revising a paper on the Loglan machine grammar for intended publication in the Communications of the ACM, a noted computer journal, albeit not a refereed publication. This paper was finally submitted, and was rejected.

la lojbangirz. is considering its own paper on Loglan/Lojban's formal grammar, but not until next year.

Declensions - Institute Loglan added an 'animal' declension proposed over a year ago by Bob McIvor. The change adds a large number of gismu to that version of Loglan which differ from each other only in the final vowel. A broader proposal for a broader set of declensions, applying to all Institute Loglan gismu, was never formalized, and is no longer being considered.